kidney disease dog med

Kidney Disease in Dogs: Signs, Symptoms, and Treatment

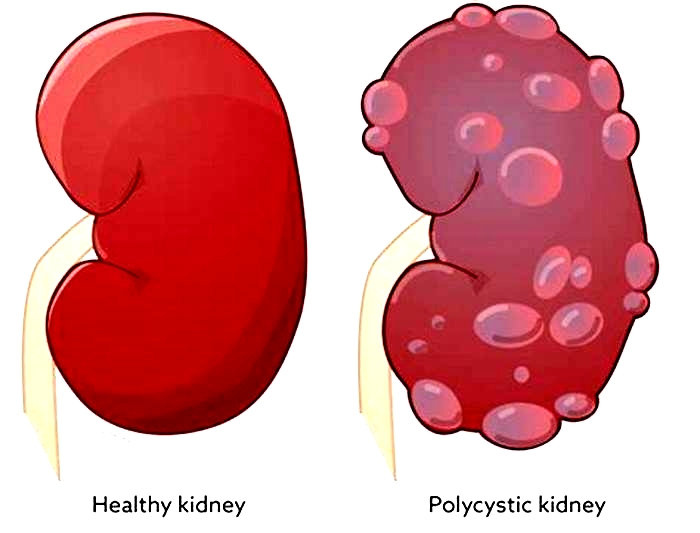

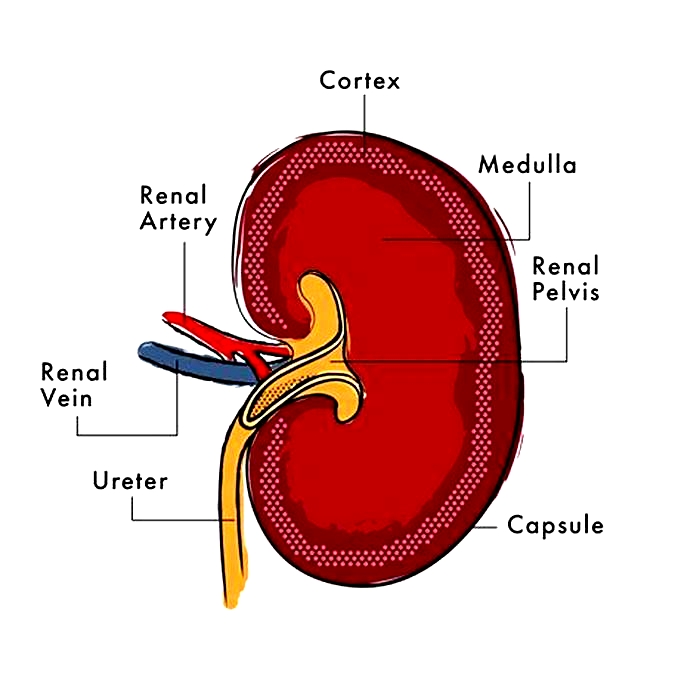

Your dogs kidneys are essential organs that filter waste products from the bloodstream. When the kidneys are weakened, either by acute or chronic kidney disease, your dogs health could suffer. Because kidney disease progresses over time, its important to learn the common symptoms so tha you can recognize them. If you catch kidney disease in dogs early on, treatment can slow down the progression and allow your dog to live longer.

What Is Kidney Disease in Dogs?

Kidney disease in dogs is sometimes called renal or kidney insufficiency because it occurs when a dogs kidneys stop doing their job as efficiently as they should. The main job of the kidneys is to help clear and excrete waste products from the blood and convert them to urine, says Dr. Jerry Klein, Chief Veterinary Officer for the AKC. If the kidneys are not working properly, these waste products can build up in the blood, causing detrimental effects.

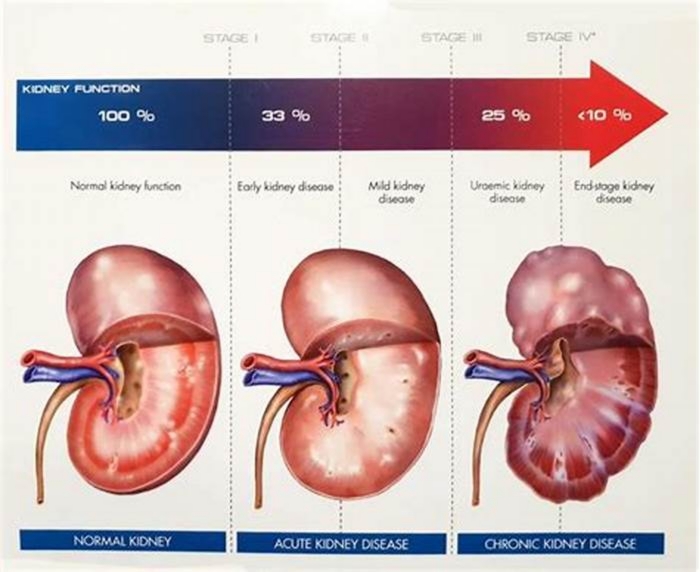

Dogs can get either acute kidney disease, which develops suddenly, or chronic kidney disease (CKD), which develops slowly and worsens over an extended period. Both involve loss of kidney function, but they result from different circumstances. Acute kidney disease is a sudden attack or injury to the kidney, whereas chronic kidney disease is a slow, degenerative loss of kidney function, Dr. Klein explains.

What Causes Kidney Disease in Dogs?

Dr. Klein warns that kidney disease could be caused by a lot of things, including infection (such as with the bacteria that causes leptospirosis), trauma, genetics, drugs, toxins, cancer, mechanical obstructions (like kidney stones), and degenerative diseases (where the job and form of the affected body part get worse over time). Anything that decreases blood flow to the kidneys, such as dehydration or heatstroke, can cause the kidneys to fail.

Acute kidney disease in dogs can be caused by exposure to hazardous materials, including toxic plants such as lilies, certain drugs, harmful foods such as grapes or raisins, or antifreeze. Puppy-proofing your home and yard can keep your dog away from potentially harmful items or foods that could be toxic.

Chronic kidney disease in dogs is also associated with growing older. Because kidney tissue cant regenerate once its damaged, the kidneys can wear out over time. As small-breed dogs often live longer than large-breed dogs, they tend to show early signs of kidney disease at an older age10 years old or more, compared to as young as 7 for the large breeds.

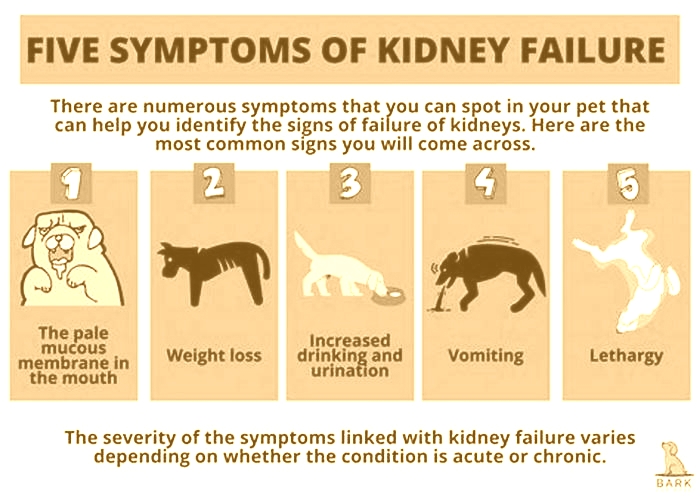

What Are the Symptoms of Kidney Disease in Dogs?

The earliest signs of kidney disease in dogs are increased urination and therefore increased thirst. Other symptoms dont usually become apparent until about two-thirds of the kidney tissue is destroyed. So, in the case of CKD, the damage may have begun months or even years before the owner notices. Because of this, its common for the signs of kidney disease in dogs to seem like they came out of the blue when in fact, the kidneys have been struggling for a long time.

Other signs of chronic kidney disease in dogs to watch for include:

Dr. Klein says there are some rarer symptoms of kidney disease in dogs to be aware of, as well. On occasion, there can be abdominal painurinary obstructions or stonesand in certain instances, one can see ulcers in the oral or gastric cavity. In extreme cases, little or no urine is produced at all.

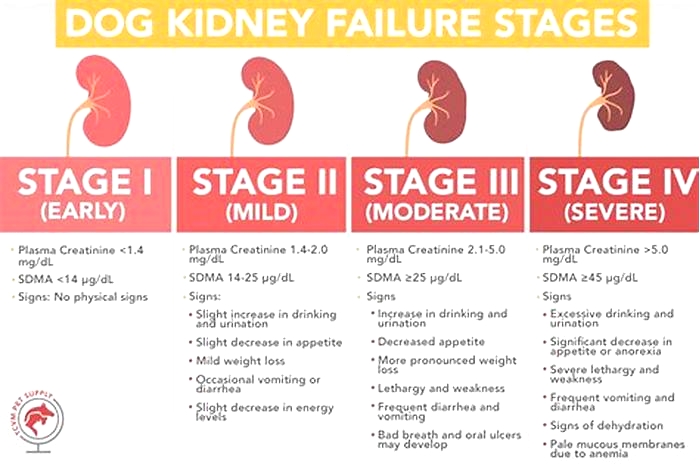

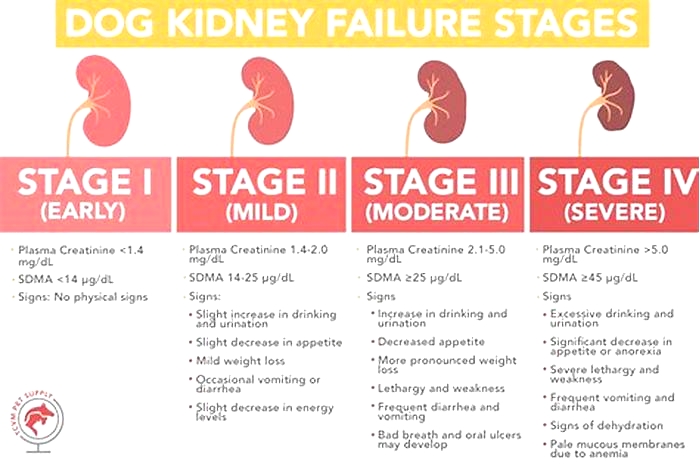

What Are the Stages of Chronic Kidney Disease in Dogs?

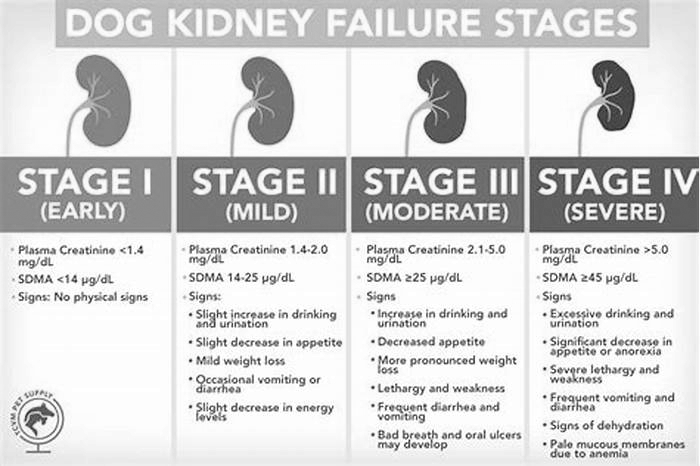

Kidney disease in dogs is measured in stages. Many veterinarians use the IRIS scale, which has four stages. Blood work measurements like creatinine and SDMA (biomarkers for kidney function) allow your vet to assign your dog to a particular stage which will determine the exact treatment.

Dr. Klein explains, The stages determine how well the kidneys can filter waste and extra fluid from the blood. As the stages go up, the kidney function worsens. In the early stages of CKD, the kidneys are still able to filter out waste from the blood. In the latter stages, the kidneys must work harder to filter the blood and in late stages may stop working altogether.

How Is Kidney Disease in Dogs Treated?

Dialysis (a medical procedure that removes waste products and extra fluid from the blood) is far more common in humans than in dogs, although peritoneal (kidney) dialysis can be performed in some cases. On rare occasions, surgical kidney transplant is possible in dogs.

But Dr. Klein specifies that depending on the type and stage of kidney disease, the main treatments for CKD are diet changes and administration of fluids, either directly into the veins (intravenous) or under the skin (subcutaneous). The balancing and correction of electrolytes are extremely important in the management of kidney patients, he explains.

Proper nutrition is needed, and there are many available diets formulated for cats and dogs with kidney issues, some by prescription only. Your veterinarian can help guide you to the most appropriate diet for your pet.

Because kidney disease, particularly in the late stages, can cause a dog to lose their appetite, it can be difficult to encourage your dog to eat enough. Dr. Klein advises, There are medications used as appetite stimulators available, such as the prescription drug mirtazapine. Capromorelin has recently been FDA-approved for dogs to address appetite in chronic kidney disease.

When Do You Need to Call Your Vet?

The prognosis and expected life span for a dog with kidney disease depend on the type of disease, the speed of progression, and underlying conditions present in the dog. However, the more serious the disease, the poorer the outcome. Thats why its so crucial to catch the illness early on.

According to Dr. Klein, In chronic kidney disease, there are methods, such as diets and medications, that can be used to lessen the burden of work the kidneys need to do and may help slow down the progression from one stage to the next. In acute kidney disease, there is less time and fewer choices available to prevent further damage to the kidneys and to try to jump-start the kidneys to get them to function normally.

Regular veterinary exams, including bloodwork, are an excellent way to spot kidney problems before the outward symptoms become apparent. And if you notice any of the above signs, dont hesitate to get your dog to the vet for further testing. It can make a huge difference in preserving kidney function and your dogs well-being for as long as possible.

Renal Dysfunction in Small Animals

With appropriate therapy, animals can survive for long periods with only a small fraction of functional renal tissue, perhaps 5%8% in dogs and cats. Recommended treatment varies with the stage of the disease. In Stages 1 and 2, animals usually have minimal clinical abnormalities. Efforts to identify and treat the primary cause of the disease should be thorough. The identification and supportive treatment of developing complications (eg, systemic hypertension, potassium homeostasis disorders, metabolic acidosis, bacterial urinary tract infection) should be aggressively pursued. The systemic hypertension seen in ~20% of animals with CKD may be seen at any stage and is not effectively controlled by feeding a low-salt diet. The usual antihypertensive medications for blood pressure substages AP2 and AP3 ( see Table: Substages of Chronic Kidney Disease Based on Arterial Blood Pressure (AP) Measurements and Risk of Target Organ Damage) are a calcium-channel blocker such as amlodipine besylate (for dogs: 0.06250.25 mg/kg, PO, every 24 hours; for cats: 0.6251.25 mg/kg, PO, every 24 hours) or an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor such as enalapril or benazepril (0.250.5 mg/kg, every 24 hours) or an angiotensin-receptor blocker (ARB) such as telmisartan (for cats the initial dose is 1.5 mg/kg, PO, every 12 hours for 14 days, followed by 2 mg/kg, PO, every 24 hours, and the dose may be reduced by 0.5-mg/kg increments to a minimum of 0.5 mg/kg, PO, every 24 hours; for dogs the dose is 1 mg/kg, PO, every 24 hours). If an ACE inhibitor is used in conjunction with a renal diet, potassium should be carefully monitored. Hyperkalemia may develop, particularly in Stage 4, and dietary change or dosage adjustment should be considered if serum potassium exceeds 6.5 mEq/L. While ACE inhibitors (or ARBs) and calcium-channel blockers may be administered together, a calcium-channel blocker is usually recommended as initial therapy in cats and an ACE inhibitor (or ARB) in dogs. In addition to providing a continuous supply of fresh drinking water and encouraging (and documenting) adequate dietary intake, body condition scoring should be used routinely to assess adequacy of intake. Animals in this stage should be fed standard, commercially available maintenance diets, unless they are markedly proteinuric (see below). All affected animals should be reevaluated every 612 mo, or sooner if problems develop.

In Stages 2 and 3, the principles for management of complications are the same, except that the animal should be evaluated every 36 mo. These evaluations should include hematology, serum biochemistries, and urinalysis. Because dogs and cats with CKD are prone to development of bacterial urinary tract infections, urine culture should be performed annually and any time urinalysis suggests infection. The progressive nature of this disease produces a vicious cycle of progressive renal destruction. Measures that may slow this progression include dietary phosphorus restriction, dietary fish oil supplementation, antihypertensive agents (for hypertensive dogs and cats), and administration of ACE inhibitors or ARBs (proteinuria substage P; see Table: Substages of Chronic Kidney Disease Based on Proteinuria). Dietary restriction of phosphate and acid load is essential in this stage, and specialized diets for management of kidney disease should be fed. Potassium citrate or sodium bicarbonate, given PO, may be indicated if the animal is severely acidotic (plasma bicarbonate <15 mEq/L) or remains acidotic 23 wk after diet change. Ifdietary restriction of phosphorus is unsuccessful in maintaining a normal level of serum phosphorus within 23 mo, phosphate-binding gels containing calcium acetate, calcium carbonate, calcium carbonate plus chitosan, lanthanum carbonate, or aluminum hydroxide should be administered with meals to achieve the desired effect. There is also a clear rationale forthe inclusion of dietary n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in these stages.

In late Stage 3 and Stage 4, all of the principles of managing the preceding stages apply, except that the animal should be evaluated every 13 mo. Dietary restriction of protein may relieve some of the signs of uremia. High-quality protein (eg, egg protein) should be fed at a level of 22.8 g/kg every 24 hours for dogs and 2.83.8 g/kg every 24 hours for cats. Commercial diets formulated for cats and dogs with CKD generally meet this recommendation. Administration of a proton pump inhibitor such as omeprazole (0.51 mg/kg, PO, every 24 hours) or an H2-receptor antagonist such as famotidine (1 mg/kg, PO, every 12 hours) decreases gastric acidity and vomiting. Anabolic steroids, such as oxymethalone or nandrolone, have been administered to stimulate RBC production in anemic animals, but this is not effective.

Recombinant erythropoietin and other erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (eg, darbopoietin, continuous erythropoietin receptor activator) may stimulate RBC production, but antierythropoietin antibodies develop in ~50% of animals treated with the human recombinant erythropoietin, epoetin alfa, and may result in refractory anemia. Darbopoietin may be less likely to produce this effect and may be preferred. Until species-specific products become generally available, erythropoietin administration is now recommended only for animals with clinically apparent signs of anemia (eg, weakness, marked lethargy not attributable to other factors), which generally occurs at a hematocrit <20%.

Fluid therapy with polyionic solutions, given IV or SC in the hospital or SC by owners at home, is often beneficial in animals with intermittent signs of uremia. Oral vitamin D administration may reduce uremic signs and prolong survival, particularly in dogs. However, vitamin D administration requires prior resolution of hyperphosphatemia (goal is serum phosphorus <6 mg/dL), and it may induce hypercalcemia. Probiotic medications and certain dietary fibers may enhance gut catabolism of nitrogenous compounds and uremic toxins. Feeding tubes may help manage chronic anorexia. Euthanasia or renal replacement therapy (renal transplantation and/or dialysis) should be carefully considered if therapy does not improve renal function and alleviate signs of uremia.