dog kidney disease and seizures

Life Expectancy of a Dog with Seizures [Vet Answers]

This article was updated on February 14th, 2024

There are many possible causes of seizures, and some are more manageable than others. Some dogs with seizures can live long and happy lives and have normal lifespans. However, the medical conditions causing the seizures may also get worse over time resulting in more frequent or more intense seizures.

In this article, our veterinarians Dr. Alex Crow & Dr. Jamie Whittenburg explain life expectancy for different types of seizures and share when euthanasia is the best option.

Key highlights: Seizures that last over 5 min or occur more than 2-3 times within 24 hours can be immediately life threateningDogs with well-controlled idiopathic epilepsy may live normal lifespans Seizures in dogs can be caused by many conditions, such as cancer, or liver and kidney disease. This article explains life expectancy for 8 different conditions If your dog continues to have uncontrolled seizures daily or weekly, humane euthanasia is often one of the kindest things you can do for them

Frequent or long seizures can be immediately life threatening

The frequency and length of seizures will have a huge impact on your dogs prognosis and life expectancy. Seizures that last over 5 minutes or occur more than 2-3 times within 24 hours can be immediately life threatening as the blood and energy supply to the bain is cut off. Therefore, these situations are an emergency, and your dog should be seen by a veterinarian immediately.

How long can a senior dog live after seizures?

On the other hand, dogs with well-controlled idiopathic epilepsy can live long and happy lives: dogs with idiopathic epilepsy have an estimated survival time of about 66 months (5.5 years) according tothis study, if seizures are properly controlled. Our Veterinarian Director Dr. Whittenburg explains:

With the newer medications that have fewer side effects and cause less strain on the liver, I believe a dog with well-controlled idiopathic epilepsy should be expected to live a normal lifespan.

Dr. Jamie Whittenburg

Veterinarian DirectorDr. Whittenburg adds however that uncontrollable epileptic seizures, or the need for medications that tend to have more negative effects on the liver, such as phenobarbital, may potentially shorten the expected lifespan. The veterinary Center for University of Missouri estimates that 60-70 percent of epileptic dogs achieve good seizure control when their therapy is carefully monitored.

If seizures are occurring due to a brain lesion such as a tumor, then the median survival time will be dramatically reduced to closer to 8 months.

It is therefore crucial to determine the cause of seizures and to start your dog on medication if necessary. In the next section, we will look at the most frequent conditions causing seizures in dogs, and their impact on life expectancy.

Most frequent conditions causing seizures (with life expectancy information for each)

Dogs of all ages and breeds can experience seizures for different causes. Here are 8 of the most common causes, including information on life expectancy and euthanasia:

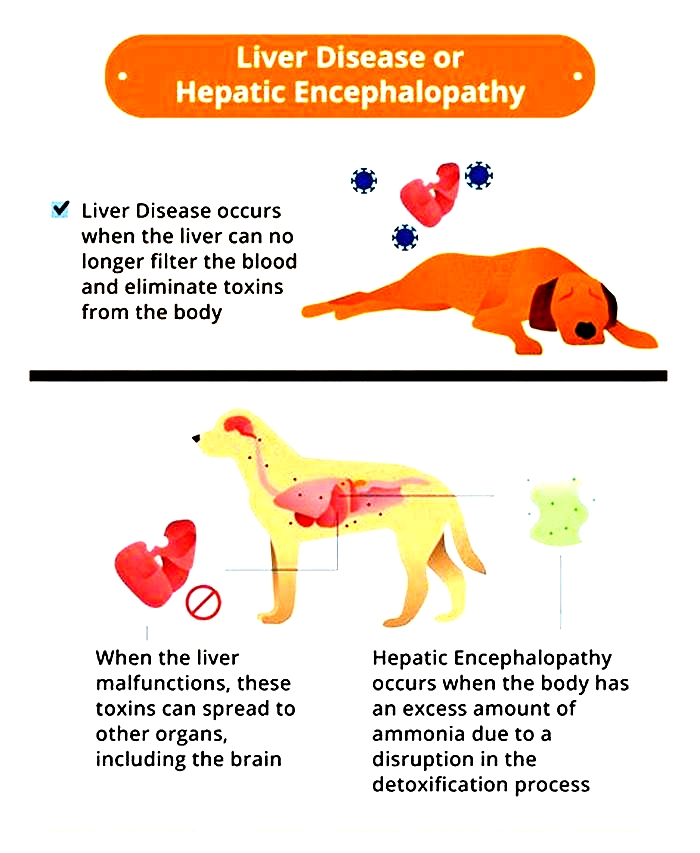

1. Liver Disease

Liver disease or failure in senior dogs can cause seizures, but other symptoms usually appear first, including loss of appetite, abdominal swelling, or digestive upsets (vomiting, diarrhea, or constipation).

Life expectancy: Dogs with liver disease can have a variable life expectancy depending on the underlying cause of the disease: some liver diseases are slowly progressive such as chronic hepatitis whereas other forms of liver disease progress much faster such as liver cancer. Because of this, the life expectancy for a dog with liver disease can range from months to years.

When it is time to consider euthanasia: If your dog is obviously very unwell and having seizures on a regular basis such as multiple seizures every week, its likely time to consider euthanasia.

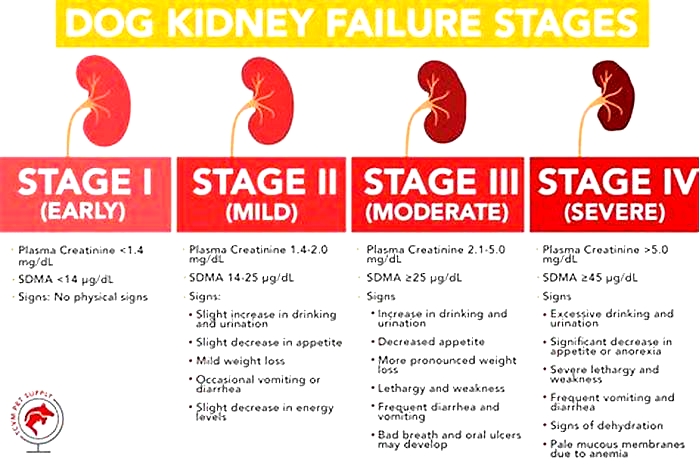

2. Kidney Disease

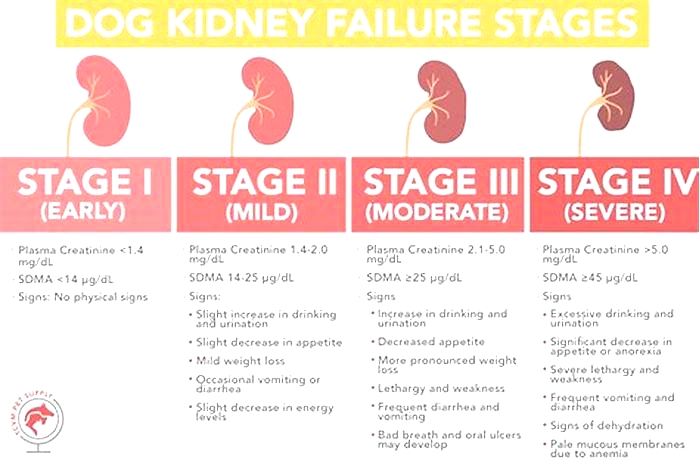

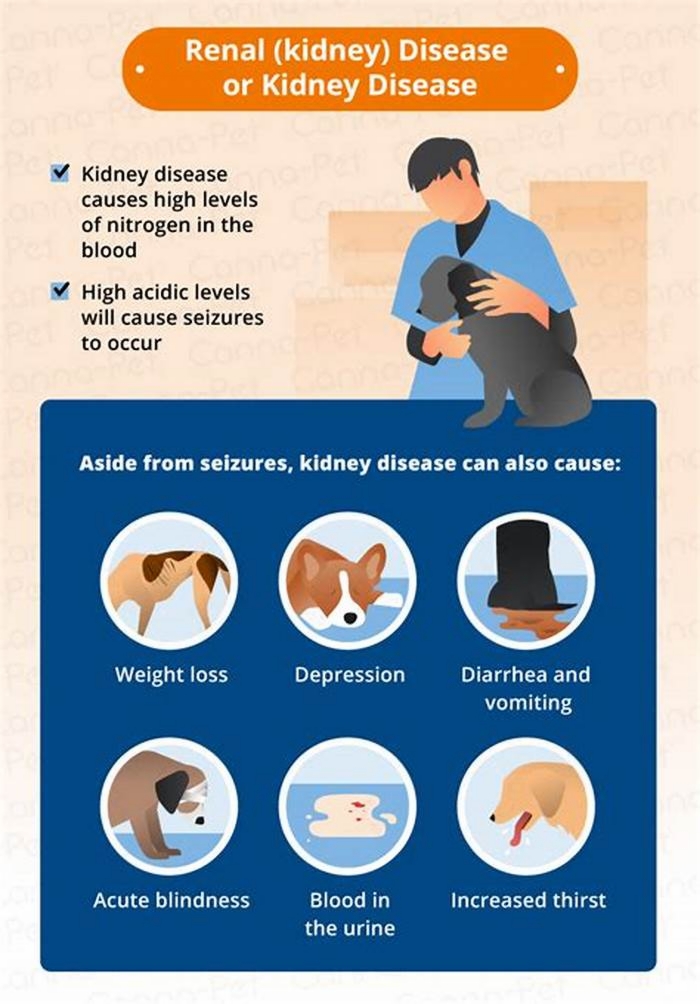

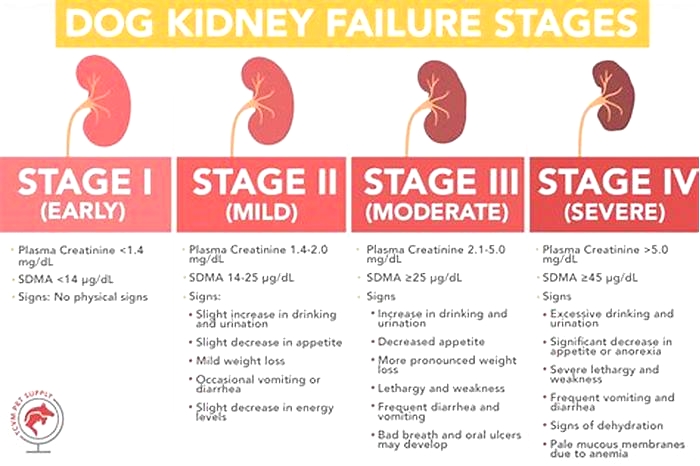

Kidney disease or failure in older dogs can lead to toxin buildup in the bloodstream, causing seizures. Usually, seizures or comas only occur in advanced stages of the disease.

Life expectancy: The life expectancy of dogs with kidney disease will depend on the stage of kidney failure they are in. Seizures will usually only occur in very late-stage renal failure; this is described as stage 4 kidney disease and the medial survival time for dogs in this category is between 14-80 days according to the international renal interest society (IRIS).

When it is time to consider euthanasia: Dogs in stage 4 renal failure are likely to be very unwell and so euthanasia may be in their best interests, especially if they are losing weight, vomiting, and having regular seizures.

3. Cancer

A brain tumor can cause seizures as well as other neurological symptoms. A cancer that starts off in another part of the body can metastasize (spread) to other parts of your dogs body, including the brain, and cause similar problems.

Life expectancy: The life expectancy of dogs with brain tumors will vary depending on the type of cancer present and the speed at which it progresses. However, in many cases, the prognosis is poor. Without treatment, survival can be short, typically weeks to months. Treatment options like surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy can extend survival to several months to a year or more.

When it is time to consider euthanasia: Treatment may be able to extend this period but often not by much. If your dog is displaying neurological symptoms other than seizures such as incoordination, confusion, and an inability to walk properly, then its time to consider euthanasia. Having your dog euthanized is also recommended if your dog is having multiple seizures a week that cannot be controlled with medication.

4. Diabetes

Dogs with extreme diabetes can enter a state known as diabetic ketoacidosis. This results in electrolyte disturbances within the blood and seizures may follow. Its also possible for seizures to occur as a result of overtreating diabetes they could have a seizure if they develop hypoglycemia because of accidentally receiving too much insulin.

Life expectancy: The general median survival time for dogs with diabetes left untreated is 60 days. Treated and controlled diabetics may live full life spans. However, if your dog is having seizures or displaying other unusual neurological activity, then they are likely in a much later stage of the disease (See our article on the Final Stages of Diabetes). Take your dog to the vet immediately as prompt treatment may be able to reverse the seizures.

When it is time to consider euthanasia: If your dog has been having seizures for a while, and their diabetes is getting more difficult to control then euthanasia may be an option. Learn more in our article Signs that Your Dog May be Dying from Diabetes.

5. Hypoglycemia

Hypoglycemia is a condition where the blood sugar level in your dog drops significantly. This can lead to seizures or coma, which are the most severe consequences of hypoglycemia.

Life expectancy: Most causes of hypoglycemia can be easily reversed through veterinary treatment. However, in some cases where there is a more serious underlying cause, the prognosis might be poorer.

When it is time to consider euthanasia: If your dog keeps experiencing seizures despite veterinary intervention, then euthanasia might be in their best interests.

Related articles about dog seizures:Can Seizures Be Fatal to Dogs?Best Food for Dogs with Seizures

6. Adverse Reaction to Medication

All medications (and also, to a lesser degree, natural remedies) can have side effects. Many are mild and can include vomiting, diarrhea, and reduced appetite. Other severe reactions are less common, but definitely do happen. Seizures in dogs can be one fairly rare, but serious, side effect of certain medications.

7. Environmental Toxins

There are several things in our dogs environment that can potentially cause seizures. These include:

- Rodent poison

- Antifreeze

- Insecticides

- Garden weedkiller

- Insect poisons

- Lead paint

- Black mold

You may not even know that things like black mold, or lead paint are in your home. If your dog has unexplained seizures, having your ductwork and heating/ac and any old paintwork checked out is a good idea. Blood tests can determine lead levels too.

Dr. Alex Crow

Veterinarian8. Trauma or Injury

An injury to the brain can cause a seizure in dogs of any age. Older dogs are more prone to falling than younger ones, and a fall down some steps resulting in a blow to the head could cause brain damage or bleeding. If your dog shows any signs of illness, strokes, or seizures after falling or injuring himself (even if you didnt see them hit their head), take them to be examined by a veterinarian asap.

You may consider humane euthanasia if your dog experiences daily or weekly seizures

Whether your dog has had one seizure or multiple, they are never considered normal. If your dog presents with seizures alone or seizures with other symptoms, seek veterinary help immediately. Your vet can run tests to determine the cause of their seizures and see if treatment options exist to ease their suffering.

While making the decision to euthanize your pet is an extremely difficult one, watching them suffer is something no owner wants to experience. Seizures are very distressing for both you and your dog, and they are likely to feel very disorientated between episodes, as Dr. Crow explains:

Seizures are very distressing for both you and your dog. Dogs are likely to feel very disorientated between episodes. Seizures are never normal, and if they are occurring on a frequent basis, veterinary attention is required.

Dr. Alex Crow

VeterinarianIf your dog is having uncontrolled daily or weekly seizures due to an illness, disease, or accident, often the kindest thing is to have them humanely euthanized. As heart-breaking as it can be to say goodbye to our pets, you can help end their suffering in the most pain-free way possible.

Final Words

While making the decision to euthanize your pet is an extremely difficult one, watching them suffer is something no owner wants to experience.

If your dog continues to seize on a weekly or even daily basis then it is not fair to keep them alive; often the kindest thing is to have them humanely euthanized.

Alex Crow, VetMed MRCVS, is an RCVS accredited Veterinary surgeon with special interests in neurology and soft tissue surgery. Dr Crow is currently practicing at Buttercross Veterinary Center in England. He earned his degree in veterinary medicine in 2019 from the Royal Veterinary College (one of the top 3 vet schools in the world) and has more than three years of experience practicing as a small animal veterinarian (dogs and cats).

View all posts

Disclaimer: This website's content is not a substitute for veterinary care. Always consult with your veterinarian for healthcare decisions. Read More.

Use of Levetiracetam in Epileptic Dogs with Chronic Kidney Disease: A Retrospective Study

1. Introduction

Epilepsy, which affects 50 million people around the world, is the most common neurological disorder [1]. In veterinary medicine, epilepsy is also the most common neurological disorder [2]. The key treatment for this condition is antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), of which the most commonly used are phenobarbital and potassium bromide [3]. However, seizures are not well controlled in 2030% of dogs with epilepsy [4]. Additionally, dogs can experience severe adverse effects with conventional AED treatment [4]. For these patients, the assessment of new AEDs for the management of epilepsy is essential [5].

Levetiracetam (LEV) is a structurally novel AED that was approved for use in humans as an adjuvant drug for partial-onset seizures in 1999 [6]. LEV is not metabolized via the hepatic cytochrome P450 system [7]. Because of its minimal hepatic metabolism, LEV is favored for use in geriatric or critical patients [7,8,9]. Furthermore, in human medicine, LEV has a minimal effect on the distribution of other AEDs because of its unique metabolic pathway [7,8,9]. Therefore, LEV is particularly favored when initiating polytherapy [10]. Accordingly, LEV has particular uses in special populations [7,8,9]. Based on its encouraging results in treating human epilepsy, levetiracetam is being used frequently in veterinary medicine, especially in dogs [11]. However, there are scant reports of its use in special populations of veterinary patients.

Compared to other AEDs, LEV has a broad margin of safety [7,8]. However, in human medicine, some patients experience undesirable side-effects and toxicity, particularly in special populations, including renal, hepatic, or cardiac insufficiency [12,13]. The usual drug dosage is established for individuals with normal renal function and metabolism [13]. In patients with impaired renal and/or hepatic function, the elimination of drugs may be markedly reduced [9,13]. In such patients, the conventional dosage regimen causes drug accumulation [13,14]. Therefore, in special populations, identifying pharmacokinetic alterations is important to guide prescription strategies [12].

The half-life of LEV elimination is extended to 1011 h in elderly human patients, and this is also extended in patients with renal disease [12,13]. Therefore, LEV dosing is adjusted in patients with impaired renal function according to the status of the patients renal function [12]. Numerous studies in human medicine report individualized LEV dosing according to the status of the patients renal function [8,9,12,13]. However, there are not reports concerning individualized LEV dosing according to the status of the patients renal status in veterinary medicine.

Evaluating the use of LEV in preexisting CKD dogs was the goal of this retrospective study, resulting in the need for dose adjustment in patients with kidney disease.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

For this retrospective study, the patient databases of the Seoul National University Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital (SNU VMTH) were searched for cases where LEV had been prescribed. The study period was between 5 January 2011 and 28 December 2019. In total, 138 dogs received LEV over a period of 9 years. Hospital records for all eligible patients were reviewed. Information and data necessary for patient evaluation were obtained from the medical records using an electronic chart program (E-friends; pnV, Jeonju, Korea).

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

The patient inclusion criteria of this study were as follows: (1) dogs with the presence of seizure or epilepsy and who were treated with oral LEV; (2) who had been diagnosed with or without CKD before LEV administration; (3) and were administered oral LEV for 7 days.

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

The patient exclusion criteria of this study were as follows: (1) patients who had not been screened for kidney impairments before LEV administration; (2) who were lost to follow up; (3) or who were missing serum blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, or phosphorus (P) data.

2.4. Blood Test Results Analysis

At least 12 h after fasting, blood samples were taken. The components of the blood tests were as follows: BUN, creatinine, P, and symmetric dimethylarginine (SDMA) levels. To determine the effects of LEV on patients kidney condition, we compared the blood test results before and after LEV treatment. The LEV-pretreatment blood test results were collected within 1 month prior to starting LEV administration. The LEV post-treatment results were obtained between 2 and 64 days after starting oral LEV administration according to patients condition and revisit interval.

Serum BUN was evaluated using standard definitions for clinically significant differences from baseline [15,16]. In patients with normal or low baseline BUN values, a relevant increase in serum BUN was defined as a 25% increase over the upper normal limit, and for patients with initially greater than normal BUN values, a 25% increase higher than baseline was considered [15,16]. Serum creatinine and p values were evaluated following the same method as the one used for serum BUN evaluation.

2.5. CKD Evaluation Using the IRIS CKD Diagnosis Guidelines

We investigated whether CKD, defined by the International Renal Interest Society (IRIS) CKD diagnostic guidelines, had been diagnosed before starting LEV administration. CKD staging (CKD stages 14) was determined according to the IRIS guidelines for staging CKD [17]. All available information, including serial serum creatinine concentrations, urinalysis, and diagnostic imaging findings, were used for the diagnosis of CKD and for the determination of the CKD stage, before starting LEV administration [17].

2.6. Epilepsy Frequency and Days Prior to and during LEV Treatment

The data collected from the patient records included age and weight at the start of LEV treatment, the total number and days of epilepsy prior to starting LEV administration, and the total number and days of epilepsy occurring during LEV treatment. The total number of epilepsy incidents during LEV treatment that occurred within 1 month after starting LEV administration was counted [18]. Additionally, the total number of days on which epilepsy occurred during the 1 month after starting LEV treatment was counted [18].

2.7. Levetiracetam Administration

All of the patients in this study were given a daily maintenance dose of LEV (Keppra; UCB Pharma SA, Belgium; Levetiracetam; Rhino Bio, Daejeon, Korea) per os (PO), depending on the patients status, and side-effects and therapeutic responses were monitored. LEV was administered at an initial dose of 10.045.0 mg/kg PO, q812h. The LEV dose was adjusted based on clinical response. LEV was used as the primary or as an add-on therapy, depending on the patients conditions. When used as add-on therapy, LEV was used in combination with phenobarbital, potassium bromide (KBr), zonisamide, or diazepam.

Side-effects of oral LEV were recorded; in particular, whether the following variable symptoms were more frequently provoked during LEV treatment was monitored: ataxia, sedation, decreased appetite, polydipsia, vomiting, diarrhea, hypersalivation, and behavior changes (showing aggression) [10,11,18]. The side-effects that occurred during LEV treatment were monitored for 1 month after the start of LEV.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using commercial software (R package, ver. 3.1.1; The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Analytical data are presented as mean standard deviation (SD). Data are presented as median with range and SD. Differences between the variables from the CKD group and the non-CKD group were tested using Fishers exact test or the chi-square test. p-values < 0.05 were regarded significant.

3. Results

3.1. Study Animals

In total, 138 dogs with seizure or epilepsy were given oral LEV over a period of 9 years, of which 62 patients met the inclusion criteria. A further 25 patients were excluded based on the exclusion criteria. Finally, 37 dogs were included in this study. We divided these patients into a CKD group (n = 20) and a non-CKD group (n = 17).

The CKD group included 20 dogs with a mean age of 12.53 3.78 years (range, 2.5817.5 years) and a median weight of 5.03 2.78 kg (range, 1.813.1 kg) when treatment with LEV began (). Several breeds were included, with the Maltese being the most common (20%) (). Dogs included both intact and neutered females and males (). The CKD groups etiological diagnoses are presented in .

Table 1

Characteristics of patients with the CKD group/non-CKD group in the present study.

| CKD Group (n = 20) | Non-CKD Group (n = 17) | |

|---|---|---|

| Variables | No. of Dogs (%) | No. of Dogs (%) |

| CKD stage before LEV administration | ||

| non-CKD | 0 (0%) | 17 (100%) |

| CKD stage 1 | 12 (60%) | 0 (0%) |

| CKD stage 2 | 8 (40%) | 0 (0%) |

| CKD stage 3 or 4 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Breeds | ||

| Maltese | 4 (20%) | 7 (41.18%) |

| Yorkshire Terrier | 2 (10%) | 2 (11.76%) |

| Pekingese | 2 (10%) | 0 (0%) |

| Cocker Spaniel | 2 (10%) | 2 (11.76%) |

| Poodle | 2 (10%) | 0 (0%) |

| Mixed breed | 2 (10%) | 3 (17.65%) |

| Chihuahua | 0 (0%) | 2 (11.76%) |

| Afghan Hound | 0 (0%) | 1 (5.88%) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 3 (15%) | 4 (23.53%) |

| Male castrated | 3 (15%) | 4 (23.53%) |

| Female | 4 (20%) | 1 (5.88%) |

| Female spayed | 10 (50%) | 8 (47.06%) |

| Body weight at start of LEV, kg | ||

| Mean SD (range) | 5.03 2.78 kg(range, 1.813.1 kg) | 5.44 5.56 kg(range, 1.2525.5 kg) |

| Age at start of LEV, years (minmax years) | ||

| Mean SD (range) | 12.53 3.78 years(range, 2.5817.5 years) | 10.26 3.73 years(range, 2.0817.25 years) |

Table 2

LEV-based therapy in dogs of the CKD group/non-CKD group.

| CKD Group (n = 20) | NonCKD Group (n = 17) | |

|---|---|---|

| Variables | No. of Dogs (%) | No. of Dogs (%) |

| Indications of LEV | ||

| Undiagnosed epilepsy | 11 (55%) | 6 (35.30%) |

| Idiopathic epilepsy | 3 (15%) | 3 (17.65%) |

| Hydrocephalus | 1 (5%) | 3 (17.65%) |

| Hydrocephalus with syringohydromyelia | 2 (10%) | 1 (5.88%) |

| Chiari-like malformation | 0 (0%) | 2 (11.76%) |

| Meningoencephalitis of unknown etiology | 1 (5%) | 0 (0%) |

| Hydrocephalus with meningoencephalitis of unknown etiology | 0 (0%) | 1 (5.88%) |

| Geriatric vestibular disease suspected | 1 (5%) | 0 (0%) |

| Reactive epilepsy | 1 (5%) | 0 (0%) |

| Brain tumor | 0 (0%) | 1 (5.88%) |

| Variables | Value | Value |

| Initial dose of LEV administered | ||

| Mean SD (range) | 21.94 8.36 mg/kg (range, 10.045.0 mg/kg) | 20.58 8.72 mg/kg (range 10.030.0 mg/kg) |

| Duration of oral LEV therapy (days) | ||

| Mean SD (range) | 147.85 183.54 days (range 8613 days) | 399.82 761.05 days (range 22649 days) |

The non-CKD group consisted of 17 dogs with a mean age of 10.26 3.73 years (range, 2.0817.25 years) and a median weight of 5.44 5.56 kg (range, 1.2525.5 kg) when LEV treatment began (). Several breeds were recorded, with Maltese once again being the most frequent (), and both intact and neutered males and females were included (). The non-CKD groups etiological diagnoses are also presented in .

3.2. Pre-Existing CKD Evaluation Based on IRIS CKD Diagnostic Guidelines

In the CKD group, most patients (60%) were CKD stage 1, while the remainder were CKD stage 2; there were no CKD stage 3 or 4 patients ().

3.3. LEV-Based Therapy in Both Groups

All of the patients in this study were given LEV dosages of 10.045.0 mg/kg orally, q812h. Most patients (n = 33, 89.19%) did not receive a loading dose. The mean duration of the oral LEV therapy in this study was 263.62 547.81 days (range, 22649 days days).

In the CKD group, the initial LEV dose was 21.94 8.36 mg/kg (range, 10.045.0 mg/kg) PO, q812h. In the non-CKD group, this dose was 20.58 8.72 mg/kg (range 10.030.0 mg/kg) PO, q812h (). The mean duration of the oral LEV therapy in the CKD group was 147.85 183.54 days (range, 8613 days), and in the non-CKD group it was 399.82 761.05 days (range, 22649 days) ().

Of the 20 CKD patients, 10 patients (50%) received LVE monotherapy, while the others received LEV in combination with phenobarbital, KBr, zonisamide, and diazepam. Four patients (20%) received LEV in combination with phenobarbital, two patients (10%) received LEV in combination with zonisamide, one patient (5%) received LEV in combination with diazepam, one patient (5%) received LEV in combination with phenobarbital and zonisamide, one patient (5%) received LEV in combination with phenobarbital and potassium bromide, and one patient (5%) used all 5 drugs simultaneously.

Of the 17 non-CKD patients, 9 patients (52.94%) received LEV monotherapy. Two patients (11.76%) received LEV in combination with phenobarbital, one patient (5.88%) received LEV in combination with zonisamide, one patient (5.88%) received LEV in combination with phenobarbital and zonisamide, one patient (5.88%) received LEV in combination with phenobarbital and diazepam, two patients (11.76%) received LEV in combination with zonisamide and gabapentin, and one patient (5.88%) received LEV in combination with phenobarbital, KBr, and zonisamide simultaneously. No drug interactions with LEV were identified among the study patients.

3.4. Outcomes of Patients on LEV Therapy

In the CKD group, the mean number of seizures prior to starting LEV was 59.7 161.7 (range, 0735), and the mean number of seizure days before LEV was 17.55 30.96 (range, 0122) (). In the non-CKD group, the mean number of seizures prior to starting LEV was 42.59 71.313 (range, 1275), and the mean number of seizure days prior to LEV treatment was 16.65 25.72 (range, 189) (). The total number of seizures and the total days of seizures during LEV treatment during the 1 month after the start of LEV treatment was 13.55 38.89 (range, 0162) and 2.8 7.05 (range, 030), respectively, in the CKD group (). In the non-CKD group, during LEV treatment, the total mean number of seizures while on LEV treatment was 7.18 12.60 (range, 048), and the total mean number of seizure days while on LEV treatment was 1.59 1.94 (range, 06) ().

Table 3

Seizure frequency of the CKD group/nonCKD group.

| CKD Group (n = 20) | NonCKD Group (n = 17) | |

|---|---|---|

| Variables | Value | Value |

| Epilepsy frequency prior to LEV treatment | ||

| Mean SD (range) | 59.7 161.70(range, 1735) | 42.59 71.31(range, 1275) |

| Days of epilepsy prior to LEV treatment | ||

| Mean SD (range) | 17.55 30.96(range, 1122) | 16.65 25.72(range, 189) |

| Epilepsy frequency during LEV treatment | ||

| Mean SD (range) | 13.55 38.88(range, 0162) | 7.18 12.60(range, 048) |

| Days of epilepsy during LEV treatment. | ||

| Mean SD (range) | 2.8 7.05(range, 028) | 1.59 1.94(range, 06) |

In general, the side-effects of LEV include ataxia, sedation, anorexia, polydipsia, vomiting, diarrhea, hypersalivation, and behavior changes (showing aggression). Of the 37 patients, 26 patients (70.27%) showed adverse effects during LEV administration. Most patients showed more than one side-effect at the same time (). More dogs in the CKD group were reported to have adverse effects than in the non-CKD group, and there was a statistically difference between the two groups (85% vs. 52.94%, p = 0.033). In the CKD group, a significant increase in sedation was identified during LEV treatment compared to baseline, but it was not statistically significant compared to the non-CKD group (55 versus 41.18%, p = 0.40). No dogs showed life-threatening adverse effects.

Table 4

Side-effects of the oral LEV were observed in the CKD group/nonCKD group.

| CKD Group(n = 20) | NonCKD Group(n = 17) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | No. of Dogs (%) | No. of Dogs (%) | p-Value |

| Any adverse event | 17 (85%) | 9 (52.94%) | 0.033 |

| Sedation | 11 (55%) | 7 (41.18%) | 0.40 |

| Ataxia | 5 (25%) | 3 (17.65%) | NA |

| Anorexia | 9 (45%) | 2 (11.76%) | NA |

| Polydipsia | 2 (10%) | 0 (0%) | NA |

| Vomiting | 7 (35%) | 1 (5.88%) | NA |

| Diarrhea | 3 (15%) | 2 (11.76%) | NA |

| Hypersalivation | 3 (15%) | 0 (0%) | NA |

| Behavior changes (showing aggression) | 1 (5%) | 0 (0%) | NA |

3.5. Clinically Relevant Increases in Serum BUN, Creatinine, and Phosphorus after LEV Administration

When all of the eligible patients were considered, the occurrence of clinically relevant increases in serum BUN, which consider the magnitude of the increase in relation to the baseline value, was statistically significantly different between the CKD group and the non-CKD group (p = 0.028; ). The incidence of clinically relevant increases in serum creatinine (p = 0.003; ) and in both serum BUN and creatinine concurrently (p = 0.014, ) was statistically significantly different between the groups. However, there was no significant difference in the occurrence of clinically relevant increases in serum phosphorus between the groups (p = 0.50; ).

Table 5

Clinically relevant serum BUN, creatinine, and phosphorus increase in the CKD group/nonCKD group.

| CKD Group(n = 20) | NonCKD Group(n = 17) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | No. of Dogs (%) | No. of Dogs (%) | p-Value |

| BUN elevation | 9 (45%) | 2 (11.76%) | 0.028 |

| Phosphorus elevation | 2 (10%) | 0 (0%) | 0.50 |

| Creatinine elevation | 8 (40%) | 0 (0%) | 0.003 |

| BUN and creatinine elevation | 6 (30%) | 0 (0%) | 0.014 |

4. Discussion

In human patients with impaired renal function, levetiracetam (LEV) dosing is individualized depending on the status of the patients renal function [7,9,12,13], but in veterinary medicine, there have been no reports on individualized LEV dosing according to the status of the patients renal function to date, and there have been few studies on the use of LEV in particular dog populations [19,20]. Thus, the impact of oral LEV on dogs with pre-existing CKD has not been previously reported; the present study provides insights into this matter.

The initial LEV dose was 21.94 8.36 mg/kg (range, 10.045.0 mg/kg) PO, q812h in the CKD group, and 20.58 8.72 mg/kg (range 10.030.0 mg/kg) PO, q812h, in the non-CKD group in this study. In humans, the elimination half-life of LEV is extended in patients with renal impairment [7,8,9,12,13], and LEV dosing is therefore adjusted according to the status of the patients renal function [8,9,12]. Pharmacokinetic studies suggest a dose of LEV 20 mg/kg, q8h to obtain plasma concentrations in normal dogs, which is similar to clinically significant plasma concentrations in humans [21,22]. Consequently, these studies suggest that dogs with renal impairments should be given a LEV dose < 20 mg/kg, q8h [21,22]. It is estimated that some of our CKD patients had higher LEV concentrations than the therapeutic range, as they were administered LEV at doses that were more than 20 mg/kg, q8h [21,22]. We did not obtain serum concentrations of LEV. However, based on previous studies, we assumed that LEV serum concentrations might be higher in the CKD group than in the non-CKD group, which was also concordant with our other study results. Statistically significantly higher number of dogs in the CKD group were reported to have side-effects than those in the non-CKD group (85% vs. 52.94%, p = 0.033). Further study is necessary to determine individualized LEV dosing according to the status of a dogs renal function.

In comparison to other AEDs, LEV has a broad margin of safety [7,8]. In this study, LEV was used as add-on therapy or primary therapy. Many patients in the current study had concurrent diseases because they were middle-aged or older. Because of the minimal hepatic metabolism, LEV is favored for geriatric or critical human patients [7,8,9]. Furthermore, in human medicine, LEV has been shown to have minimal effects on the distribution of other AEDs due to its unique metabolic pathway [7,8,9]. Therefore, the use of LEV in specific complex medical situations, particularly in polytherapy, has been encouraged [10]. In this study, we found that LEV was mostly well tolerated in dogs, but it was not free from side-effects.

In general, the side-effects of LEV include ataxia, sedation, anorexia, polydipsia, vomiting, diarrhea, hypersalivation, and behavior changes (aggression) [10,11,18]. In this study, most patients showed more than one side-effect simultaneously. In the CKD group, there was a significant increase in sedation during LEV administration compared to at baseline, but this increase was not remarkably different from the one observed in the non-CKD group (p = 0.40). Because of sedation, chronic recurrent dehydration associated with periodic water intake may occur [23], which can be problematic, particularly in CKD patients. A key management factor in CKD patients is access to fresh water anytime because the ability to concentrate urine and excrete water is impaired in CKD patients [24]. If a patient with CKD is sedated, water intake may be irregular, which may accelerate dehydration [23], decreasing blood flow to the kidneys [24]. Consequently, uremic toxins are retained [24]. This was supported by the results of the present study. In the CKD group, nine patients (45%) demonstrated clinically significant increases [15,16] in serum BUN () and eight demonstrated clinically relevant increases in serum creatinine (). Moreover, in that group, six patients (30%) had concurrent clinically significant increases [15,16] in serum BUN and creatinine (). On the other hand, in the non-CKD group, there were no clinically significant increases in BUN and/or creatinine (). Therefore, canine CKD patients who are administered LEV should be monitored, and they may require physical and/or laboratory evaluation for dehydration [25,26].

The statically significant difference in the incidence of clinically relevant increases in serum BUN and/or creatinine between the CKD and non-CKD groups () may be due to the acute kidney injury (AKI) that is superimposed on pre-existing CKD. In human medicine, although it has been shown that kidney function can fully recover after overcoming an AKI, cumulative observational data have revealed that AKI can worsen underlying CKD [27]. There have been four case reports in humans where LEV was identified as a possible contributor to AKI [25,26,28,29]. Based on those reports, patients taking LEV who present with abdominal pain, oliguria, nausea/vomiting, and a high creatinine concentration may require laboratory assessment for hidden renal adverse effects [25,26], and renal function during treatment with LEV should be monitored [25,26,28,29]. In the differential diagnosis for any unexplained acute renal failure, AKI due to LEV should be considered [28]. However, in veterinary medicine, there have been no reports of renal toxicity attributed to LEV, and further studies are necessary to assess renal toxicity that is secondary to LEV in dogs.

As in other retrospective studies, this study had some limitations. First, we had some missing values, such as serum SDMA values, which increase during CKD progression and that correlate strongly with a decrease in the glomerular filtration rate [30,31], because the data were collected retrospectively and SDMA has only been included in the diagnostic criteria for the diagnosis of CKD since 2015 [32]. We rarely measured SDMA values before this time-point. Therefore, future studies including SDMA results are needed. Second, in this study, the patients were chronically ill because they were middle-aged or older. Consequently, it is possible that the CKD stage might have been falsely high or falsely low [17,24]; the CKD stage of the patients with prerenal azotemia could have been falsely high [17,24], and that of patients who had lost muscle mass could have been falsely low [17,24]. In retrospective studies, it is difficult to solve this issue. Third, we did not measure the plasma LEV concentration values, as there is no therapeutically effective LEV concentration known in dogs [10]. Therefore, in practice, LEV concentration monitoring is rarely performed [10]. However, based on previous studies, it could be assumed that the CKD group had higher LEV concentrations than the non-CKD group did [7,8,9,21,22]. Lastly, our data could not exclude the possibility that other AEDs (such as phenobarbital, potassium bromide, zonisamide, or diazepam) contributed to anti-epileptic effects or adverse effects. It was also difficult to control the dosage of LEV, owner compliance, and factors in the living environment, such as diet. Further prospective and controlled studies are needed.