acute kidney failure for dogs

Kidney Disease in Dogs: Signs, Symptoms, and Treatment

Your dogs kidneys are essential organs that filter waste products from the bloodstream. When the kidneys are weakened, either by acute or chronic kidney disease, your dogs health could suffer. Because kidney disease progresses over time, its important to learn the common symptoms so tha you can recognize them. If you catch kidney disease in dogs early on, treatment can slow down the progression and allow your dog to live longer.

What Is Kidney Disease in Dogs?

Kidney disease in dogs is sometimes called renal or kidney insufficiency because it occurs when a dogs kidneys stop doing their job as efficiently as they should. The main job of the kidneys is to help clear and excrete waste products from the blood and convert them to urine, says Dr. Jerry Klein, Chief Veterinary Officer for the AKC. If the kidneys are not working properly, these waste products can build up in the blood, causing detrimental effects.

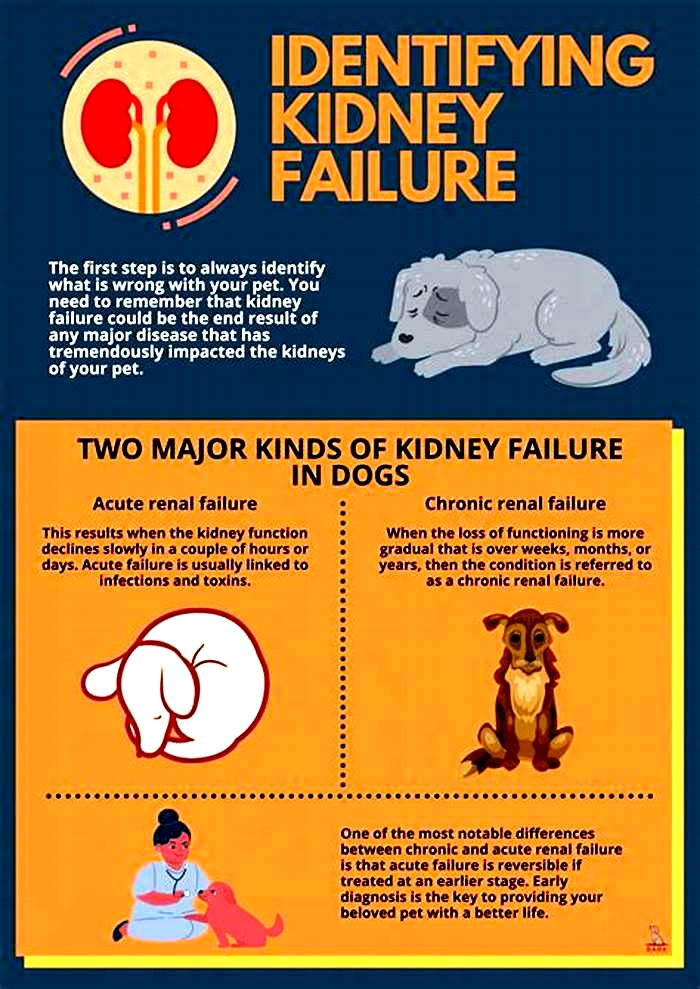

Dogs can get either acute kidney disease, which develops suddenly, or chronic kidney disease (CKD), which develops slowly and worsens over an extended period. Both involve loss of kidney function, but they result from different circumstances. Acute kidney disease is a sudden attack or injury to the kidney, whereas chronic kidney disease is a slow, degenerative loss of kidney function, Dr. Klein explains.

What Causes Kidney Disease in Dogs?

Dr. Klein warns that kidney disease could be caused by a lot of things, including infection (such as with the bacteria that causes leptospirosis), trauma, genetics, drugs, toxins, cancer, mechanical obstructions (like kidney stones), and degenerative diseases (where the job and form of the affected body part get worse over time). Anything that decreases blood flow to the kidneys, such as dehydration or heatstroke, can cause the kidneys to fail.

Acute kidney disease in dogs can be caused by exposure to hazardous materials, including toxic plants such as lilies, certain drugs, harmful foods such as grapes or raisins, or antifreeze. Puppy-proofing your home and yard can keep your dog away from potentially harmful items or foods that could be toxic.

Chronic kidney disease in dogs is also associated with growing older. Because kidney tissue cant regenerate once its damaged, the kidneys can wear out over time. As small-breed dogs often live longer than large-breed dogs, they tend to show early signs of kidney disease at an older age10 years old or more, compared to as young as 7 for the large breeds.

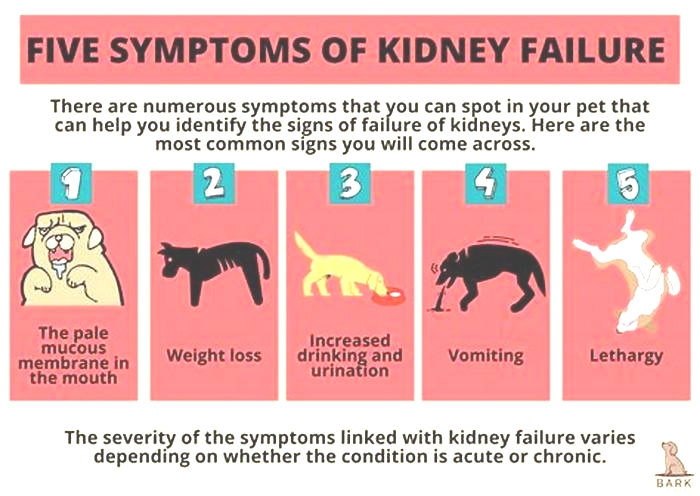

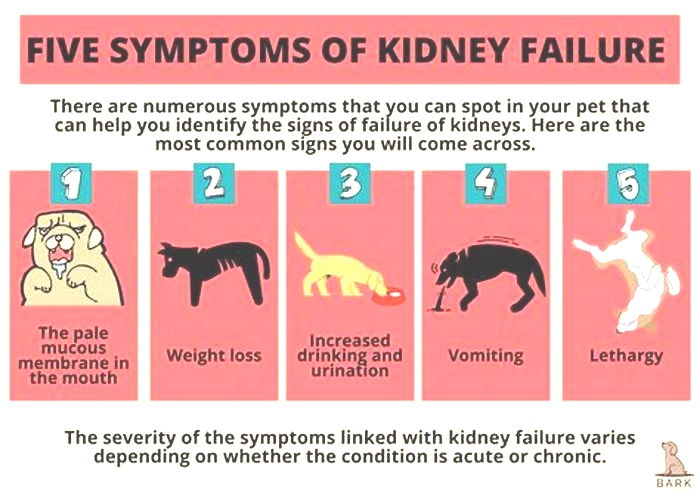

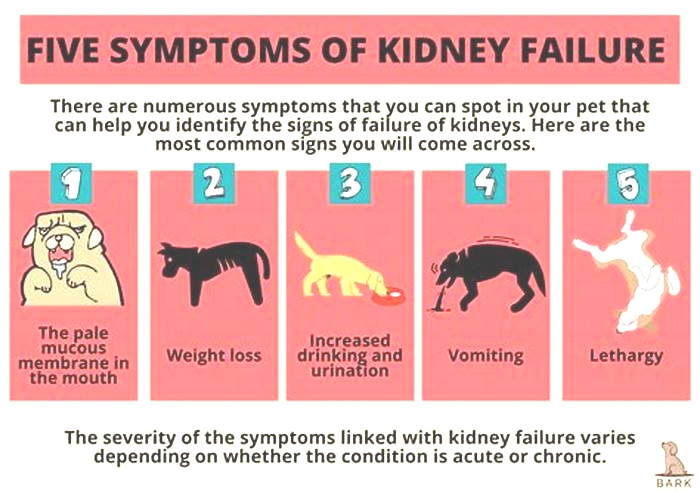

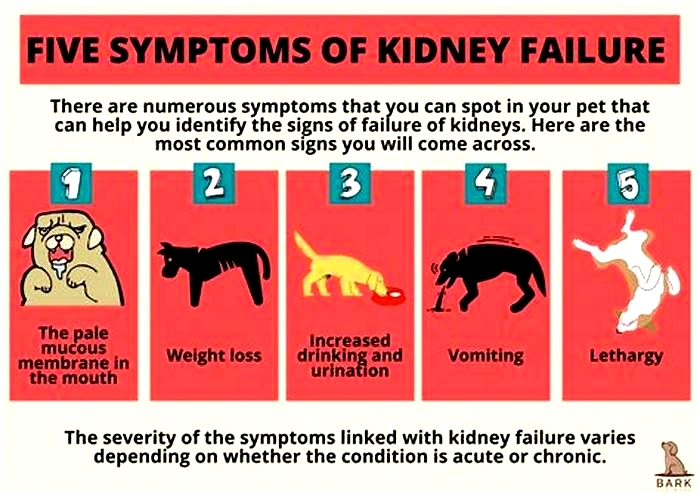

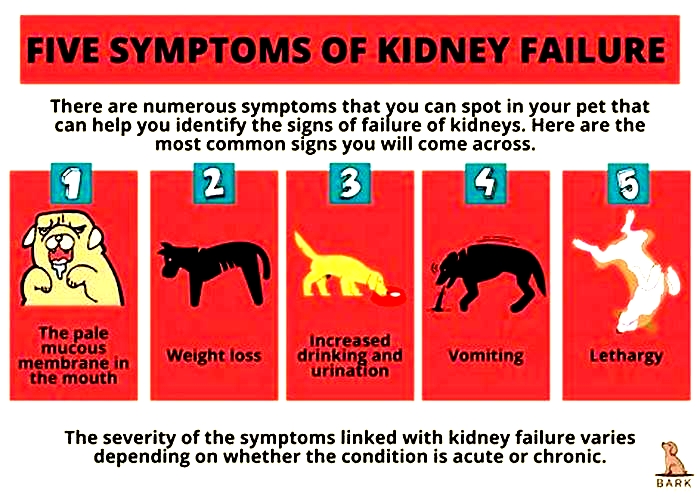

What Are the Symptoms of Kidney Disease in Dogs?

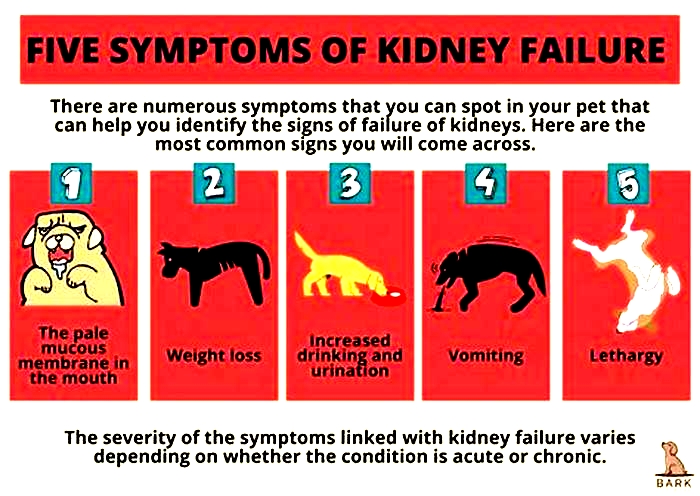

The earliest signs of kidney disease in dogs are increased urination and therefore increased thirst. Other symptoms dont usually become apparent until about two-thirds of the kidney tissue is destroyed. So, in the case of CKD, the damage may have begun months or even years before the owner notices. Because of this, its common for the signs of kidney disease in dogs to seem like they came out of the blue when in fact, the kidneys have been struggling for a long time.

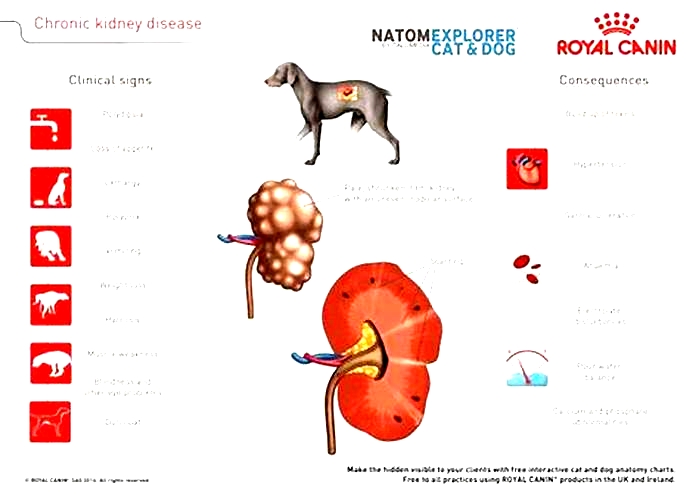

Other signs of chronic kidney disease in dogs to watch for include:

Dr. Klein says there are some rarer symptoms of kidney disease in dogs to be aware of, as well. On occasion, there can be abdominal painurinary obstructions or stonesand in certain instances, one can see ulcers in the oral or gastric cavity. In extreme cases, little or no urine is produced at all.

What Are the Stages of Chronic Kidney Disease in Dogs?

Kidney disease in dogs is measured in stages. Many veterinarians use the IRIS scale, which has four stages. Blood work measurements like creatinine and SDMA (biomarkers for kidney function) allow your vet to assign your dog to a particular stage which will determine the exact treatment.

Dr. Klein explains, The stages determine how well the kidneys can filter waste and extra fluid from the blood. As the stages go up, the kidney function worsens. In the early stages of CKD, the kidneys are still able to filter out waste from the blood. In the latter stages, the kidneys must work harder to filter the blood and in late stages may stop working altogether.

How Is Kidney Disease in Dogs Treated?

Dialysis (a medical procedure that removes waste products and extra fluid from the blood) is far more common in humans than in dogs, although peritoneal (kidney) dialysis can be performed in some cases. On rare occasions, surgical kidney transplant is possible in dogs.

But Dr. Klein specifies that depending on the type and stage of kidney disease, the main treatments for CKD are diet changes and administration of fluids, either directly into the veins (intravenous) or under the skin (subcutaneous). The balancing and correction of electrolytes are extremely important in the management of kidney patients, he explains.

Proper nutrition is needed, and there are many available diets formulated for cats and dogs with kidney issues, some by prescription only. Your veterinarian can help guide you to the most appropriate diet for your pet.

Because kidney disease, particularly in the late stages, can cause a dog to lose their appetite, it can be difficult to encourage your dog to eat enough. Dr. Klein advises, There are medications used as appetite stimulators available, such as the prescription drug mirtazapine. Capromorelin has recently been FDA-approved for dogs to address appetite in chronic kidney disease.

When Do You Need to Call Your Vet?

The prognosis and expected life span for a dog with kidney disease depend on the type of disease, the speed of progression, and underlying conditions present in the dog. However, the more serious the disease, the poorer the outcome. Thats why its so crucial to catch the illness early on.

According to Dr. Klein, In chronic kidney disease, there are methods, such as diets and medications, that can be used to lessen the burden of work the kidneys need to do and may help slow down the progression from one stage to the next. In acute kidney disease, there is less time and fewer choices available to prevent further damage to the kidneys and to try to jump-start the kidneys to get them to function normally.

Regular veterinary exams, including bloodwork, are an excellent way to spot kidney problems before the outward symptoms become apparent. And if you notice any of the above signs, dont hesitate to get your dog to the vet for further testing. It can make a huge difference in preserving kidney function and your dogs well-being for as long as possible.

Kidney Failure in Dogs

What Is Kidney Failure in Dogs?

The primary job of the kidneys is to filter the blood by removing waste products and controlling the amount of fluid and nutrients kept in the body and how much is passed in urine.

With any type of kidney failure, this filtering isnt working well, so waste products are not properly removed from the bloodstream and too much fluid is passed in urine along with proteins and electrolytes. As waste products build up in the blood and tissues, dogs can get ulcerations (tears) in the lining of their digestive tract as well.

Kidney failure may also be referred to by terms listed below. The word renal refers to all things related to kidneys, and is often used interchangeably. Failure, insufficiency, and disease are commonly used to describe similar issues with the kidneys.

Kidney disease is often divided into categories based on how long it has been affecting the dog. Acute renal failure occurs in a very short time frame, and is often caused by eating or drinking a toxin or getting a severe infection that harms the kidneys. Chronic kidney disease refers to a process with a more gradual onset or one that has been happening for a longer period of time.

Changes that can occur with an aging pet are often caused by chronic kidney disease, but if a dogs kidneys were damaged by eating a toxic item several months ago and he now has renal failure because of this, it is also known as chronic kidney disease.

Symptoms of Kidney Failure in Dogs

Drinking more water (polydipsia)

More frequent urination (polyuria)

Urinary accidents in house-trained pets

Lack of energy

Refusing to eat

Vomiting

Drooling

Changes in defecation (either diarrhea or constipation)

Weight loss

Mouth sores

Bad breath

Weakness

Causes of Kidney Failure in Dogs

Kidney failure can occur because of an acute event, such as a toxin ingestion or infection that harms the kidneys; degenerative (worsening) changes over time; or an underlying medical condition that damages renal tissues, which can occur due to genetic predispositions in some dog breeds.

Specific causes include:

Ingested toxins

Metabolic diseases

Kidney infections

Autoimmune disease

Cancers

Breeds that are prone to inherited renal failure include:

How Veterinarians Diagnose Kidney Failure in Dogs

Your veterinarian will want to run several tests, in addition to a physical exam, to diagnose kidney failure, such as:

Complete blood count

Chemistry panel

Urinalysis with culture

Abdominal ultrasound

Treatment of Kidney Failure in Dogs

Treatment of kidney failure is based on the severity of the disease and whether it is acute or chronic.

Acute kidney disease is treated with hospitalization and IV fluid therapy to support the kidneys and help them remove wastes. Depending on the cause of the disease, decontamination medications, toxin-binding medications, antibiotics, or medications to support the gastrointestinal tract may be given. In extreme cases, renal dialysis can help the kidneys. This last procedure is rare, only available at some university or veterinary specialty hospitals.

Chronic kidney disease requires careful management of dogs at home. They need to have access to water at all times and be encouraged to drink water. Many dogs have improvements with a prescription kidney diet. Some dogs need to be on medications to control high blood pressure or to protect their stomach. Pets with chronic kidney disease need to see their veterinarian often so that their renal values can be checked. Some dogs with kidney disease need to receive injectable fluids at home or may even need to be hospitalized at times to help their fluid needs.

Recovery and Management of Kidney Failure in Dogs

With acute kidney failure, prognosis is variable depending upon the cause of the disease, how severe the disease is, how damaged the kidneys are, the speed and aggressiveness of treatment, and the dogs response.

For chronic renal failure, long-term prognosis is not good. Most dogs die or are euthanized within a year because of poor quality of life.

The families of dogs with kidney disease should expect to watch them closely and will need to see their veterinarian often, especially as their pets kidney function gets worse. These dogs will be easily dehydrated, as their kidneys are not able to keep water in their bodies. Any infection, vomiting, diarrhea, or changes in appetite or activity could severely dehydrate the pet and worsen the disease.

Kidney Failure in Dogs FAQs

How does kidney failure differ from kidney disease?

Kidney disease is a broader term that includes any problem with the kidneys. Kidney failure is a specific term that means the kidneys cant keep up with filtering waste products and managing fluid levels.

Is kidney failure fatal in dogs?

Depending on the severity and progression of the disease, kidney failure can be fatal.

WRITTEN BY

Laura Russell, DVM, MBA, DABVPVeterinarian

Dr. Russell is a 2003 graduate of the University of Missouri. She is board certified in Canine and Feline Practice, certified in canine...

Acute kidney injury in dogs: Etiology, clinical and clinicopathologic findings, prognostic markers, and outcome

1.INTRODUCTION

Acute kidney injury (AKI) leading to severe uremia is associated with high morbidity and death.1, 2 Despite advances in management of AKI and the increased availability of renal replacement therapies, the overall case fatality rate remains as high as 45% to 60% for dogs managed medically or with hemodialysis.1, 2, 3, 4

Multiple factors are involved in the pathophysiology of AKI in dogs. The most common etiologies include ischemia, inflammation, exposure to nephrotoxins, and infectious diseases.1, 3, 5 These influence the outcome of animals with AKI. Yet, despite comprehensive diagnostic workup, in a substantial portion of animals with AKI the etiology is unknown at presentation and remains unknown throughout the disease course, thus in these cases the etiology cannot contribute to prognostic projections.2

Hospitalacquired AKI is not considered a leading etiology for AKI in veterinary medicine. Conversely, it is a common cause of AKI in human patients, and even a mild increase in serum creatinine (sCr) concentration during hospitalization increases the risk for inhospital death.6, 7 Over recent decades, advanced treatment options (eg, ventilation) became available for veterinary patients, resulting in longer hospitalization periods and management of animals with multiple problems and comorbidities, similarly to human medicine. Such intensive care, along with the establishment of more sensitive criteria, increased awareness and new guidelines for the diagnosis of AKI have likely led to higher prevalence and awareness of hospital acquired AKI.8

In previous studies of AKI in dogs, the degree of azotemia, anemia, proteinuria, electrolyte abnormalities, decreased urine production, increased anion gap, and involvement of other (ie, extra renal) organ systems were identified as risk factors for death.1, 8 Among these, anuria is a relatively consistent risk factor for death.1, 8, 9

The last largescale retrospective study evaluating AKI in dogs was published approximately 25years ago.1 Since then, multiple changes have occurred in veterinary medicine, including a shift in etiologies,2, 3 new guidelines for the diagnosis and management of AKI, and advancement in therapeutic capabilities, all of which potentially influence the outcome of dogs with AKI.

The objectives of this study were to: (a) characterize the etiology, clinical and clinicopathologic findings and outcome in a large cohort of dogs diagnosed with AKI and (b) identify risk factors for death.

2.MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Dogs and definitions

The medical records of dogs diagnosed with AKI at the Koret School of Veterinary Medicine, The Robert H. Smith Faculty of Agriculture, Food and Environment, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, were retrospectively reviewed (years 20152021). Data extracted from the electronic medical records included signalment, history and physical examination findings at presentation, CBC, serum biochemistry, urinalysis, urine culture, blood gas analysis, blood pressure measurements, ultrasonographic findings, hospitalization length, and outcome. AKI was diagnosed based on the presence of acute onset of clinical signs consistent with AKI (eg, anuria, oliguria, polyuria, vomiting, inappetence) and based on the International Renal Interest Society (IRIS) guidelines for diagnosis and grading of AKI. Dogs with a previous diagnosis of chronic kidney disease (CKD) or ultrasonographic evidence consistent with CKD (eg, small irregular kidneys, decreased corticomedullary distinction10) were excluded, as were dogs with postrenal azotemia. Anuria was defined as urine production <0.1mL/kg/h for >6hours or by 12hours without urination in hospitalized animals receiving fluids IV. Hospital acquired AKI was defined as an increase in sCr of 0.3mg/dL within 48hours, while receiving fluids IV.8

2.2. Etiology and concurrent diseases

The etiology of AKI was classified as inflammatory/ischemic (ie, systemic underlying inflammatory process with suspected decreased tissue perfusion), infectious, nephrotoxic, other, or unknown. Inflammatory causes included pancreatitis, peritonitis (eg, septic or chemical), pyometra, severe gastroenteritis, myositis, pneumonia, disseminated intravascular coagulation, diabetic ketoacidosis, snake envenomation, and heatstroke. Pancreatitis was diagnosed based on compatible history, clinical signs, and ultrasonographic findings, or by increased serum 1,2odilaurylracglycero glutaric acid(6methylresorufin) ester (DGGR)lipase activity (reference interval [RI], <108U/L).11, 12 Nephrotoxicosis was defined on the basis of recent ingestion of grapes/raisins, or overdose of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. Infectious causes included pyelonephritis and leptospirosis. Pyelonephritis was diagnosed based on a positive urine culture, urine sediment findings (ie, pyuria and bacteriuria), and ultrasonographic findings consistent with pyelonephritis, as described.13, 14 Leptospirosis was diagnosed if the titer of a single microscopic agglutination test (MAT) was 1:800 without recent history of vaccination, or when seroconversion in paired MAT titers (ie, fourfold increase between the first and second samples) was documented. Other etiology included AKI secondary to hypercalcemia and glomerulopathies, diagnosed based on the presence of high magnitude proteinuria (urine protein to creatinine ratio [UPC]>2) after exclusion of extrarenal causes. When 2 presumptive causes were present concurrently, the primary cause was used for analysis.

Survivors were defined as animals that were discharged from the hospital and were still alive for at least 14days after discharge. Nonsurvivors either died or were euthanized because of lack of improvement and poor prognosis, despite treatment during hospitalization. Dogs were excluded from the study if euthanized within the first 24hours of admission.

2.3. Collection of samples and laboratory methods

Blood samples for CBC (Advia 120 or 2120, Siemens, Erlangen, Germany; Abacus Junior Vet, Diatron, Wien, Austria) and serum chemistry (Cobas 6000, Roche, Mannheim, Germany) were collected at presentation in potassiumEDTA and plain tubes with gel separators, respectively, and analyzed within 60minutes from collection. CBC and serum chemistry from referring clinics were considered only if obtained 24hours before admission. Urine samples were obtained within 24hours of presentation by cystocentesis for urinalysis, including dipstick chemistry (Urilux, Roche, Mannheim Germany), measurement of specific gravity by refractometry, sediment evaluation, which was done either by experienced laboratory personnel or automatically (SediVue Dx, IDEXX Laboratories, Westbrook, ME), and aerobic bacterial culture and sensitivity. Pyuria and hematuria were defined as the presence of >5 leukocytes or erythrocytes, respectively in a highpower field. Proteinuria was defined as a urine dipstick result of 1+ (ie, >30mg/dL). UPC (Cobas Integra 400 Plus or Cobas 6000, Roche, Mannheim, Germany) was only measured in dogs with severe proteinuria (urine dipstick result +4), inactive sediment, and when glomerular disease was suspected as the inciting cause for AKI.

2.4. Blood pressure measurement and therapy

Blood pressure was measured with an oscillometric blood pressure monitoring device (Midmark, Cardell touch, USA), using protocols recommended by the ACVIM Consensus Guidelines.15 The first documented blood pressure measurement within 24hours of admission and before the use of any vasoactive drugs was considered as blood pressure upon arrival. The highest recorded measurement throughout hospitalization was considered as maximal systolic (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP).

2.5. Statistical analysis

The distribution pattern of continuous variables was assessed using the ShapiroWilk test. Since some data did not distribute normally, data are presented as median and range and the MannWhitney Utest was used to compare continuous variables between 2 groups. The 2 or the Fisher's exact tests were used to examine the association between 2 categorical variables. Variables associated with death were included in a forward multivariable logistic regression analysis to further examine their association with the outcome. The Hosmer and Lemeshow test was used to assess the goodness of fit. Receiver operating curve analysis was used to determine sensitivities and specificities for outcome prediction. The optimal cutoff point was selected as the value associated with the least number of misclassification. All tests were 2tailed, and in all, P<.05 was considered significant. Analyses were performed using a statistical software package (SPSS 22.0 for Windows, IBM Corp., Armonk, New York).

3.RESULTS

The medical records search yielded 605 dogs with a suspected diagnosis of AKI during the study period. One hundred and fifty dogs were excluded because of postrenal azotemia or because of missing data in their medical records necessary to establish a reliable diagnosis of AKI. In addition, 206 dogs were excluded because of findings suggestive of preexisting CKD. Subsequently, 249 dogs met the inclusion criteria and were included in the statistical analysis.

One hundred and sixtyfour (66%) dogs survived and 85 (34%) dogs did not survive, of which 34 (40%) dogs died and 51 (60%) dogs were euthanized during hospitalization.

3.1. Signalment

The cohort included 121 males (castrated, 63; 52%) and 128 females (spayed, 99; 77%). The most common breeds were mixed (n=107), German shepherd (n=14), Labrador retriever (n=10), Cavalier king Charles spaniel and Yorkshire terrier (n=7, each), Shitzu and Maltese (n=6, each), Golden retriever, Husky, Poodle, Border collie, Vizsla, Pincher, and Pitbull (n=5, each). There was no median age difference (P=.18) between survivors (72months; range, 1216months) and nonsurvivors (84months; range, 2174months), and no difference (P=.29) in median body weight between survivors (19.3kg; range, 1.275.8) and nonsurvivors (21.3kg; range, 1.664.2).

3.2. Clinical presentation

The most common clinical signs at presentation were lethargy, anorexia, vomiting, diarrhea, polyuria, and polydipsia (Table). Diarrhea was more frequent (P=.001) among nonsurvivors, while the proportions of the other clinical signs did not differ significantly between the outcome groups (Table).

TABLE 1

Clinical findings at presentation in dogs with acute kidney injury

| Clinical sign | All dogs, n (%) | Survivors, n (%) | Nonsurvivors, n (%) | Pvalue |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lethargy | 225 (90) | 146 (89) | 79 (93) | .32 |

| Anorexia | 206 (83) | 134 (82) | 72 (86) | .43 |

| Vomiting | 168 (68) | 113 (69) | 55 (66) | .68 |

| Diarrhea | 102 (41) | 55 (34) | 47 (56) | .001 |

| Polyuria | 46 (19) | 35 (21) | 11 (13) | .11 |

| Polydipsia | 44 (18) | 34 (21) | 10 (12) | .08 |

Median respiratory rate at presentation was higher (P=.05) among nonsurvivors (36 breaths/min; range, 20160) compared with survivors (32 breaths/min; range, 988). No difference was found in the median heart rate (P=.11) and rectal temperature (P=.05) at presentation between survivors (120 beats per minute [bpm]; range, 56270 vs 38.2C; range, 34.340.6) and nonsurvivors (120bpm; range, 28240 vs 37.9C; range, 35.240.8). Anuria was documented in 62 (25%) of 245 dogs. The case fatality rate was higher among dogs with anuria compared with dogs without anuria (50% vs 28%, respectively; odds ratio [OR], 2.5, 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 1.394.6, P=.002).

3.3. Etiology

The etiology of AKI was not determined in 59 (24%) dogs. The most common putative etiologies were ischemic/inflammatory (58%), infectious (8%, of which 16 dogs [84%] with leptospirosis and 3 dogs [16%] with pyelonephritis), and nephrotoxicosis (6%; Table). Hospitalacquired AKI was documented in 23 (9%) of 249 dogs; in 5 (22%) of which, AKI was attributed to general anesthesia performed immediately before the diagnosis. The overall case fatality rate of hospitalacquired AKI was 44% and was not significantly different compared to the overall case fatality rate of other etiologies combined (P=.32).

TABLE 2

Putative etiologies of AKI in 249 dogs

| Etiology | All dogs, n (%) | Survivors, n (%) | Nonsurvivors, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ischemic/inflammatory | 144 (58) | 91 (56) | 53 (62) |

| Unknown | 59 (24) | 38 (23) | 21 (25) |

| Infectious | 19 (8) | 17 (10) | 2 (2) |

| Toxic | 14 (6) | 11 (7) | 3 (4) |

| Othera | 13 (5) | 7 (4) | 6 (7) |

Pancreatitis was diagnosed in 54 (22%) of 249 dogs, and there was no difference in the proportion of dogs diagnosed with pancreatitis between survivors and nonsurvivors (P=.85).

3.4. Hematology and serum biochemistry findings

Anemia (hematocrit, <37.1%) was documented in 67 (32%) of 212 dogs and was more common in nonsurvivors compared with survivors (29/69 [42%] vs 41/143 [29%], P=.05; Table ). Platelet count was significantly (P<.001) lower in nonsurvivors (138103/L; range, 8668103/L) compared with survivors (216103/L; range, 201509103/L), and the proportion of thrombocytopenia was higher (34/67 [51%] and (32/143 [22%], respectively, P<.001; Table 3).

TABLE 3

CBC at presentation of dogs with acute kidney injury

| Analyte | RI | All dogs | Survivors | Nonsurvivors | Pa | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Median (range) | <RI, n (%) | >RI, n (%) | n | Median (range) | <RI, n (%) | >RI, n (%) | n | Median (range) | <RI, n (%) | >RI, n (%) | |||

| WBC (103/L) | 5.9 to 13.9 | 211 | 16.3 (0.6130.0) | 18 (9) | 132 (66) | 143 | 15.6 (0.7130.0) | 11 (8) | 86 (60) | 68 | 17.4 (0.695.5) | 7 (10) | 46 (68) | .27 |

| RBC (106/L) | 5.7 to 8.8 | 211 | 6.4 (1.110.8) | 68 (32) | 18 (8.5) | 143 | 6.6 (1.910.8) | 41 (29) | 11 (8) | 68 | 6.1 (1.19.9) | 27 (40) | 7 (10) | .03 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 37.1 to 57 | 212 | 42.6 (10.772.8) | 70 (33) | 28 (13) | 143 | 43.95 (14.872.8) | 41 (29) | 18 (13) | 69 | 39.3 (10.772.4) | 29 (42) | 10 (14) | .05 |

| MCV (fL) | 58.8 to 71.2 | 211 | 67.3 (46.297.4) | 14 (7) | 42 (20) | 143 | 66.8 (53.077.0) | 9 (6) | 24 (17) | 68 | 68.2 (46.297.4) | 5 (7) | 18 (26) | .17 |

| MCHC (g/dL) | 31.0 to 36.2 | 210 | 34.1 (27.949.3) | 14 (7) | 38 (18) | 142 | 34.5 (28.649.3) | 7 (5) | 32 (23) | 68 | 33.9 (27.940.8) | 7 (10) | 6 (8) | .07 |

| RDW (%) | 11.9 to 14.5 | 208 | 15.0 (11.936.9) | 0 (0) | 126 (61) | 141 | 14.85 (11.930.5) | 0 (0) | 81 (57) | 67 | 15.2 (11.936.9) | 0 (0) | 45 (67) | .25 |

| Platelets (103/L) | 143 to 400 | 210 | 200 (81509) | 66 (31) | 33 (16) | 143 | 215 (201509) | 32 (22) | 26 (18) | 67 | 136 (8668) | 34 (51) | 7 (10) | <.001 |

Activities of ALP, ALT, AST, GGT, and concentration of bilirubin were significantly higher in nonsurvivors, whereas bloodpH, bicarbonate, albumin, and total protein were significantly lower (Table).

TABLE 4

Serum chemistry at presentation of dogs with acute kidney injury

| Analyte | RI | All dogs | Survivors | Nonsurvivors | Pa | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Median (range) | <RI, n (%) | >RI, n (%) | n | Median (range) | <RI, n (%) | >RI, n (%) | n | Median (range) | <RI, n (%) | >RI, n (%) | |||

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.0 to 4.4 | 218 | 3.3 (0.65.5) | 76 (35) | 20 (9) | 138 | 3.4 (1.35.5) | 39 (28) | 16 (12) | 80 | 3.0 (0.65.4) | 37 (46) | 4 (5) | .001 |

| ALP (U/L) | 21 to 170 | 181 | 230 (135604) | 4 (2) | 109 (60) | 119 | 180 (133496) | 2 (2) | 65 (55) | 62 | 303 (145604) | 2 (3) | 44 (71) | .04 |

| ALT (U/L) | 19 to 67 | 178 | 78 (35406) | 15 (8) | 96 (54) | 116 | 60 (33952) | 13 (11%) | 55 (47) | 62 | 93 (55406) | 2 (3) | 41 (76) | .01 |

| Amylase (U/L) | 103 to 1510 | 163 | 966 (10714981) | 0 (0) | 37 (23) | 106 | 974 (10714981) | 0 (0) | 25 (24) | 57 | 913 (33810809) | 0 (0) | 12 (21) | .30 |

| AST (U/L) | 19 to 42 | 158 | 87 (148876) | 0 (0) | 109 (69) | 104 | 69 (148876) | 0 (0) | 66 (63) | 54 | 116 (176567) | 0 (0) | 43 (80) | .003 |

| Bicarbonate (mM/L) | 20.0 to 24.0 | 172 | 17.2 (5.444.5) | 131 (76) | 11 (6) | 109 | 18.0 (6.144.5) | 76 (70) | 10 (9) | 63 | 13.7 (5.424.4) | 55 (87) | 1 (2) | <.001 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.0 to 0.2 | 198 | 0.26 (0.158.65) | 0 (0) | 118 (60) | 129 | 0.2 (0.135.2) | 0 (0) | 65 (50) | 69 | 0.4 (0.258.7) | 0 (0) | 53 (77) | <.001 |

| Calcium (mg/dL) | 9.7 to 11.5 | 167 | 9.6 (4.217.5) | 84 (50) | 14 (8) | 109 | 9.7 (6.217.5) | 53 (49) | 10 (9) | 58 | 9.4 (4.217.5) | 31 (53) | 4 (7) | .14 |

| Chloride (mM/L) | 104 to 118 | 173 | 99.1 (51121) | 124 (72) | 2 (1) | 117 | 99.1 (51.7120.5) | 84 (72) | 1 (1) | 56 | 99.2 (51119) | 40 (71) | 1 (2) | .88 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 135 to 361 | 168 | 224 (53589) | 23 (14) | 23 (14) | 108 | 226 (59529) | 11 (10) | 16 (15) | 60 | 222 (53589) | 12 (20) | 7 (12) | .35 |

| CK (U/L) | 51 to 399 | 158 | 340 (64111217) | 0 (0) | 72 (46) | 104 | 327 (6499660) | 0 (0) | 45 (43) | 54 | 392 (80111217) | 0 (0) | 27 (50) | .13 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.3 to 1.2 | 249 | 4.1 (1.137.9) | 4 (2) | 245 (98) | 164 | 3.6 (1.137.9) | 1 (1) | 163 (99) | 85 | 4.7 (1.223.1) | 3 (4) | 82 (96) | .13 |

| DGGR lipase (U/L) | 5 to 107 | 68 | 297 (1711040) | 0 (0) | 56 (82) | 48 | 269 (176348) | 0 (0) | 40 (83) | 20 | 657 (2711040) | 0 (0) | 16 (80) | .40 |

| GGT (U/L) | 0 to 6 | 156 | 5.0 (0.0540) | 0 (0) | 72 (46) | 102 | 4.0 (0.0540) | 0 (0) | 38 (37) | 54 | 7.5 (0.0212) | 0 (0) | 34 (63) | .05 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 64 to 123 | 163 | 101 (171477) | 17 (10) | 42 (26) | 106 | 100 (211280) | 10 (9) | 23 (22) | 57 | 105 (171477) | 7 (12) | 19 (33) | .22 |

| Phosphorus (mg/dL) | 3.0 to 6.2 | 198 | 8.34 (1.228) | 10 (5) | 144 (73) | 129 | 8.32 (1.224.1) | 6 (5) | 91 (71) | 69 | 9.24 (1.428.0) | 4 (6) | 53 (77) | .11 |

| Potassium (mM/L) | 3.6 to 5.3 | 245 | 4.5 (2.39.6 | 38 (16) | 55 (22) | 162 | 4.5 (2.38.8) | 24 (15) | 38 (23) | 83 | 4.4 (2.59.6) | 14 (17) | 17 (20) | .38 |

| Sodium (Mm/L) | 140 to 154 | 191 | 141 (110157) | 75 (39) | 1 (0.5) | 129 | 141 (111157) | 48 (37) | 1 (1) | 62 | 141 (110153) | 27 (44) | 0 (0) | .74 |

| Total protein (g/dL) | 5.4 to 7.6 | 167 | 5.9 (2.610.2) | 54 (32) | 21 (13) | 109 | 6.1 (3.710.2) | 29 (27) | 15 (14) | 58 | 5.6 (2.68.9) | 25 (43) | 6 (10) | .005 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 19 to 133 | 154 | 76 (14919) | 4 (3) | 45 (29) | 100 | 71 (14919) | 2 (2) | 27 (27) | 54 | 88 (14821) | 2 (4) | 18 (33) | .47 |

| Urea (mg/dL) | 10 to 54 | 225 | 169 (20670) | 0 (0) | 206 (92) | 149 | 168 (26603) | 0 (0) | 135 (91) | 76 | 177 (20670) | 0 (0) | 71 (93) | .13 |

| Venous blood pH | 7.35 to 7.45 | 173 | 7.3 (7.07.6) | 93 (54) | 9 (0.6) | 110 | 7.4 (7.17.6) | 47 (43) | 6 (5) | 63 | 7.3 (7.07.5) | 46 (73) | 3 (5) | <.001 |

Median concentration of sCr at presentation of all dogs was 4.1mg/dL (range, 1.137.9; Figure), increasing to a peak of 4.6mg/dL (range, 1.143.2). While median sCr concentration at presentation did not differ significantly between the outcome groups, median peak sCr (Figure 1) and the last median sCr during hospitalization (discharge or death) were significantly (P<.001) higher in nonsurvivors compared with survivors (5.4mg/dL [range, 0.820.9] vs 1.2mg/dL [range, 0.36.7], respectively). Maximal documented sCr was used for classifying dogs to IRIS grades: Grade I, 6 dogs (2%), Grade II, 38 dogs (15%), Grade III, 89 dogs (36%), Grade IV, 77 dogs (31%), and Grade V, 39 dogs (16%). The case fatality rate of dogs with Grade I, Grade II, Grade III, Grade IV, and Grade V was 1/6 (17%), 8/38 (21%), 23/89 (26%), 36/77 (47%), and 17/39 (44%), respectively. The overall case fatality rate significantly increased with IRIS AKI grade (P=.009). Maximal sCr as a predictor of the outcome had an area under the ROC curve of 0.65 (95% confidence interval, 0.580.73). A cutoff point of 5.3mg/dL was associated with sensitivity and specificity of 64% and 66%, respectively.

Serum creatinine concentration at presentation of survivors and nonsurvivors. Data are presented as boxes and whiskers. Each box includes the interquartile range, the horizontal line within a box represents the median, and the whiskers represent the range. Outliers are depicted by circles

3.5. Urinalysis

Median USG of all dogs was 1.018 (range, 1.0061.050) with no difference between the outcome groups (P=.69). The most common urinalysis abnormalities were proteinuria (based on urine dipstick), hematuria, pyuria, and bacteriuria (Table). Proteinuria was documented in 111 (80%) of 139 dogs with available urinalysis and was significantly more common (P=.03) in nonsurvivors (34/37 dogs, 92%) compared with survivors (77/102 dogs, 75%). Eleven dogs had a UPC measurement with a median UPC of 2.78 (range, 1.121.3). Cylinduria was present in 22 (16%) of 140 dogs including the following types: granular (13 dogs; 59%), hyaline (4 dogs; 18%), RBC (1 dog; 5%), and not specified (4 dogs; 18%). Glucosuria, in the absence of hyperglycemia, was documented in 34 (25%) of 138 dogs. Urine culture (n=77) was positive in 14 (18%) dogs with no difference in the proportion of a positive urine culture between the outcome groups (P=.52). Bacterial isolates included Escherichia coli (9 dogs; 64%), Klebsiella Pneumoniae (3 dogs; 21%), and Pseudomonas Aeruginosa (1 dog; 7%). One isolate was not specified (7%).

TABLE 5

Urinalysis abnormalities in dogs with AKI

| Analyte | Positive result, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Proteinuria | 111/139 (80) |

| Hematuria | 74/140 (53) |

| Pyuria | 66/140 (47) |

| Bacteriuria | 45/140 (32) |

| Bilirubinuria | 39/138 (28) |

| Epithelial cells | 37/139 (27) |

| Glycosuria | 34/138 (25) |

| Urobilinogenuria | 29/138 (21) |

| Positive urine culture | 14/77 (18) |

| Cylinduria | 22/140 (16) |

| Crystalluria | 12/140 (8.5) |

3.6. Blood pressure

One hundred and twentyfour dogs had documented blood pressure at presentation with overall median SBP of 143mm Hg (range, 60240mm Hg) and DBP of 88mm Hg (range, 23170mm Hg). No significant difference was found for initial SBP or DBP between the outcome groups (P=.16, .43, respectively). Twentyeight (23%) dogs were hypertensive (SBP>160mm Hg) at presentation, increasing to 64% (134/210 dogs) during hospitalization.

3.7. Dialytic intervention

Fortyseven (18.8%) dogs were treated with hemodialysis as follows: 24 (51%) dogs received continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT), 17 (36%) dogs received intermittent hemodialysis (IHD), and 6 (13%) dogs were treated with both modalities. Dogs managed by hemodialysis had significantly higher peak sCr concentration compared with dogs treated conventionally (10.1mg/dL; range, 5.543.2 vs 3.9mg/dL; range, 1.121.0, respectively; P<.001). There was no difference in case fatality rate between dogs managed conventionally or with hemodialysis (67% vs 60%, respectively, P=.31).

3.8. Hospitalization

The overall median hospitalization period was 5days (range, 072). Nonsurvivors had a shorter median hospitalization period compared with survivors (2days, range, 024 vs 6days, range, 072, receptively; P<.001). Hospitalization was significantly longer (P=.01) among dogs with an infectious etiology (median 9days, range, 117) compared with a toxic etiology (median 2.5days, range, 017) and ischemic/inflammatory etiology (median 4days, range, 024). During hospitalization, survivors had lost 0.4kg (range, 16.2 to +3.6), which represented 2% decrease in the median body weight over the hospitalization period, while nonsurvivors did not have a change in median weight (median, 0.0, range, 6.2 to +7.5kg).

3.9. Multivariable analysis

In the multivariable analysis including albumin, maximal sCr, ALT, total bilirubin, RBC, platelet count, total solids, respiratory rate, anuria, and diarrhea, only albumin concentration (P=.002), anuria (P=.002), and diarrhea (P=.003) remained significant risk factor for death.

4.DISCUSSION

Acute kidney injury is a common diagnosis in veterinary practice and is associated with high morbidity and death. Dogs sustaining AKI often require prolonged hospitalization, which is associated with substantial financial investment, and are at risk of developing CKD.1 Information regarding the case fatality rate and tools to assess the prognosis are needed for both clinical decision making and guidance of owner expectations. The ongoing shift in AKI etiologies,2 establishment of new guidelines for the diagnosis and management of AKI,16 and advancement in therapeutic capabilities (mostly the increased availability of renal replacement therapies) have all potentially enabled better outcome of dogs sustaining AKI in recent years. Indeed, the current study demonstrates a relatively low case fatality rate. The main negative prognostic indicators in this study were AKI grade, anuria, diarrhea, high respiratory rate, anemia, thrombocytopenia, lower albumin concentration, increased activities of liver and biliary enzymes as well as bilirubin concentration, and metabolic acidosis. Some of these risk factors are surrogate markers for the diseases severity and others for complications and extrarenal organs involvement.

The etiology was identified in 76% of the dogs in the study; however, some of the etiologies should be regarded as putative since it is not always feasible to prove cause and effect relationship. Inflammatory and ischemia were combined into 1 category as these conditions often coexist, making it impossible to determine the primary cause for AKI. Unknown etiology of AKI was not associated with a worse outcome, thus it should not be considered a negative prognostic factor. Ischemic/inflammatory conditions, followed by infectious causes and nephrotoxicosis, were the most common etiologies herein, in agreement with previous studies.1, 3, 5, 17 The proportion of AKI etiologies might vary among different geographical areas, possibly influencing the outcome of dogs with AKI. For example, none of the dogs in this study was diagnosed with ethylene glycol intoxication, a severe nephrotoxicosis that typically carries a grave prognosis.5, 18, 19 Leptospirosis, which is associated with a favorable outcome, was diagnosed in only 6% of the dogs, likely because of the relatively low prevalence of leptospirosis in our geographical region along with the introduction of multivalent vaccination.

The case fatality rate of dogs with an infectious etiology was not different compared to dogs with noninfectious etiologies, inconsistent with some previous studies,2, 3, 19 possibly because of the overall relatively good outcome in this study compared with other studies. The favorable outcome of dogs with an infectious etiology in previous studies is likely due to the nature of the injury (ie, reversible) and the availability of a specific treatment directed at elimination of the underlying cause (ie, leptospirosis, pyelonephritis).

Hospital acquired AKI was a relatively common cause of AKI, in accordance to the trends in human patients, accounting for 9% (23/249) of the cases in this study. This probably results from an intensive and prolong hospitalization time, as well as new guidelines for the diagnosis of AKI, sensitizing clinicians to the importance of small changes and trends in sCr during hospitalization.8, 9 Hospitalized animals often sustain severe inflammatory response and are prone to hemodynamic instability, both of which make these animals susceptible for developing AKI.

The most common clinical signs of AKI in this study were not specific and included lethargy, anorexia, vomiting, diarrhea, anuria, polyuria, and polydipsia, consistent with previous studies.1, 2, 20 These clinical signs result from accumulation of uremic toxins, other body organs involvement, as well as comorbidities and complications. The proportions of most clinical signs did not differ significantly between the outcome groups. The proportion of diarrhea was higher in nonsurvivors, potentially as a result of direct gastrointestinal damage secondary to the presence of uremic toxins, and thus correlates with the degree of azotemia, or from complications such as pancreatitis or gastrointestinal edema due to overhydration. Severe diarrhea might also be the primary cause for illness, resulting in fluid loss and dehydration that may incite AKI. Higher respiratory rate was also associated with higher case fatality rate, consistent with a previous study.2 Possible mechanisms include pulmonary edema due to overhydration, noncardiogenic pulmonary edema (resulting from severe inflammation or less likely pneumonitis), or hemorrhage.

Anuria was documented in 25% of dogs and significantly associated with case fatality rate. Decreased urine production is a consistent negative prognostic indicator in both animals and humans with AKI.1, 8, 9, 21 It is likely that decreased urine production is also a marker of the disease severity.5 Accumulation of uremic toxins in anuric and oliguric dogs is likely more rapid, resulting in severe azotemia, consequently, leaving only a narrow window of opportunity for recovery in the absence of dialytic intervention.

In agreement with previous studies in both dogs1, 2 and humans,22 anemia at presentation was recognized as a negative prognostic factor. Anemia is traditionally considered a feature of CKD rather than AKI; however, dogs with AKI admitted to secondary or tertiary referral centers in particular develop anemia because of several mechanisms including bleeding (eg, gastrointestinal), anemia of inflammation, decreased erythropoietin production (preventing adequate response to the developing anemia), as well as cumulative blood loss because of repeated sampling. It is possible that anemia associated with decreased oxygen delivery to body organs, including the kidneys, is at least partially responsible for the outcome of these dogs.23

Lower platelet number and thrombocytopenia were also more common among nonsurvivors. Although thrombocytopenia is a common feature of leptospirosis,20 the case fatality rate of dogs diagnosed with infectious etiology was lower compared with other etiologies, thus the case fatality rate of animals with thrombocytopenia cannot be explained by leptospirosisassociated thrombocytopenia, in accordance with human literature.24 Thrombocytopenia could be a complication of the kidney injury itself or an independent risk factor for the development of AKI, as has been demonstrated in people.25 Otherwise it could be attributed to the underlying illness or coagulation disorders (eg, DIC), which have been shown to be associated with increased case fatality rate in dogs with AKI.2

In accordance with previous reports,2, 26 sCr concentration at presentation was not associated with death; therefore, prognosis should not be determined based on sCr at presentation. However, both peak sCr as well as IRIS AKI grade were associated with case fatality rate in this study. The severity of azotemia and the IRIS grade delineate the window of opportunity for recovery, as uremic toxins are distributed throughout body water (ie, all body organs), subsequently leading to organ dysfunction and death. Therefore, animals with severe uremia and high IRIS grade are less likely to survive, especially in the absence of dialytic intervention. Although the degree of azotemia is a proxy to the disease severity, it does not indicate the potential for reversibility of the injury, which is highly dependent on the underlying cause.18, 19

Lower venous blood pH and bicarbonate were common and associated with a worse shortterm outcome in this study, likely representing the degree of kidney dysfunction. Serum phosphorus concentration, on the other hand, was not associated with the outcome herein, as opposed to the results of the previous large scale cohort of 99 dogs with AKI.1 It is likely that similar to sCr, variables at presentation do not represent the severity of the injury, either because the disease is progressing or because the animal has not reached a steady state.

Activities of ALP, AST, ALT, GGT, and concentration of bilirubin were significantly higher in nonsurvivors. This could be indicative of the severity of the disease manifested by extrarenal complications or otherwise reflect complications such as pancreatitis and liver injury, which might have been more severe in these dogs, attributing to their worse outcome.17, 27, 28 It has been shown that the number of organs affected by the diseases is positively associated with case fatality rate.2

The most common urinalysis abnormalities were proteinuria, hematuria, pyuria, and bacteriuria. Proteinuria was more common than previously reported.1 UPC was not available for most dogs, since animals with AKI are not in steady state, thus this variable is not being evaluated routinely in our institution in dogs with AKI, unless primary glomerular disease is suspected. Glucosuria in the absence of hyperglycemia was detected in 25% of the dogs, comparable to the incidence reported previously.1 Cylindruria, on the other hand, was only documented in 16% of the cases, which is lower than previously reported.1 These findings demonstrate once again the insensitivity of these markers for AKI.

In this study, the prevalence of systemic hypertension in dogs with AKI was relatively low at presentation compared with previous reports, but increased substantially during hospitalization, consistent with previous reports.16, 29 The increase in the occurrence of hypertension during hospitalization might relate to overhydration. Hydration status is a very subjective measure, which was assessed by multiple clinicians during the study period; therefore, these data were not included in the study because of potential bias. Nonetheless, clinicians should be extremely aware of the risk of overhydration and its consequences including hypertension. Despite its potential for damaging target organs, including the kidneys,15 there was no association between systemic hypertension and survival in this study, potentially because of close monitoring and prompt treatment. Our findings support the necessity for frequent blood pressure monitoring of hospitalized dogs with AKI, even if systemic hypertension is not documented at presentation.

Conventional medical management of AKI is aimed at identifying and eliminating the underlying cause along with supportive therapies in accordance to the clinical and clinicopathological consequences of uremia, as well as presence of complications. When the injury is severe and medical management is unlikely to control the consequences of the disease, renal replacement therapies are indicated. The latter expand the window of opportunity for recovery and thus are expected to improve the outcome.5 The availability of renal replacement therapies is increasing in veterinary medicine worldwide, however is still limited because of the need for costly equipment and trained personnel. In this study, 19% of the dogs underwent hemodialysis, emphasizing the frequent utility of this therapeutic intervention. The overall case fatality rate of dogs treated with hemodialysis (40%) is comparable to reports in human patients (32%53%),30 and apparently lower than previously reported in dogs managed with hemodialysis (48%56%).2, 18 Although there is a trend in recent years to initiate hemodialysis earlier, the perceptible favorable outcome of dogs treated with hemodialysis in this study cannot be attributed to a lower severity compared with previous reports, as sCr was comparable (10.1mg/dL vs 9.7mg/dL).2 It might be attributed to the overall enhanced care and improved knowledge and techniques of extracorporeal therapies. The case fatality rate of dogs managed with hemodialysis was not higher compared to the overall case fatality rate of animals managed medically, despite a significantly higher median sCr in the former. This finding is not in agreement with a previous report,3 but emphasizes the therapeutic potential of this modality, as most animals managed by hemodialysis were not expected to survive without dialytic intervention.

The overall case fatality rate in the present study was 34%, which is lower compared with previous studies of dogs with AKI, reporting case fatality rate (including euthanasia) ranging from 45% to 62%.1, 2, 3, 5, 17, 31, 32 A plausible explanation for the favorable outcome is earlier diagnosis as a result of implementation of the IRIS AKI guidelines. Indeed 6 dogs were diagnosed with grade I AKI. Early diagnosis promotes early intervention and close monitoring, potentially preventing the diseases to progress further, before the injury becomes irreversible and the window of opportunity for recovery narrows. The lack of irreversible etiologies, such as ethylene glycol intoxication, probably affected the outcome of this cohort. Finally, the higher survival rates might be a consequence of the significant developments that occurred in the veterinary field over the past few decades including the introduction of more advanced therapies and intensive care, comparable to human medicine.30, 33

Our study has several limitations, mainly because of its retrospective nature. The availability of complete medical records before referral was variable and some data were missing from the medical records, weakening the power of some statistical analyses, and possibly precluding identification of some causes of AKI, risk factors, and prognostic indicators. Although our institution admits first opinion cases, it is mainly a secondary and a tertiary referral center, thus cases reviewed might not accurately represent cases of AKI observed in general clinical practice. Classification of some etiologies cannot be proved and should be regarded as putative. Treatment of dogs with AKI, both during hospitalization and after discharge, was performed by different clinicians, which possibly impacted the outcome. Nonetheless, guidelines for AKI treatment in our hospital are rather uniform. This study describes the shortterm outcome only, and studies evaluating the longterm outcome of these dogs are warranted. Finally, consistent with other studies of AKI, euthanized dogs were not excluded, potentially negatively influencing the overall case fatality rate. We have tried to overcome this limitation by excluding animals that were euthanized within the first 24hours from presentation. Yet it is likely that some of the euthanized dogs might have survived providing that euthanasia was not an option, potentially affecting the risk analysis.

In conclusion, the case fatality rate of dogs with AKI is more favorable than have previously documented. Hospitalacquired AKI is common and likely increasing as medical treatment advances. This study identified several negative prognostic indicators of the severity of the disease (as reflected by presence of anuria, peak sCr concentration, AKI grade, the degree of acidemia), emphasizing the need for early diagnosis. Other negative prognostic indicators are likely surrogate markers for presence of complications and extrarenal organs affected by the disease. The utility of extracorporeal therapies and its favorable outcome as part of the management of AKI in referral centers is also demonstrated.